Evolving eResearch

Why does research practice need to evolve?

In the year 1665, the first academic journal was published: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London. That was the same year as the great plague, incidentally. New journals were quickly added so that some time in 2010, some lucky fellow wrote article fifty million. The growth has been exponential, but the mechanism for dissemination is 350 years old and it shows. At the moment, papers are being published at the rate of 1.3 per minute and rising. Most are never read, fewer still are cited. Many great ideas go undiscovered because it is simply too hard to find them. And when you do, they are still not easy to extract from the dense text of the research paper. A similar argument can be made for data and even the computational code and methods we use in research—all of these are valuable and potentially reusable outcomes.

In the year 1665, the first academic journal was published: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London. That was the same year as the great plague, incidentally. New journals were quickly added so that some time in 2010, some lucky fellow wrote article fifty million. The growth has been exponential, but the mechanism for dissemination is 350 years old and it shows. At the moment, papers are being published at the rate of 1.3 per minute and rising. Most are never read, fewer still are cited. Many great ideas go undiscovered because it is simply too hard to find them. And when you do, they are still not easy to extract from the dense text of the research paper. A similar argument can be made for data and even the computational code and methods we use in research—all of these are valuable and potentially reusable outcomes.

I no longer travel to work on a horse, nor get leeched when I have a fever, so why do we still communicate research outcomes via an outdated, static medium? The three pillars of science are: communicability, repeatability and refutability. Science cannot easily be repeated or refuted from a text in a library, but maybe 1 out of 3 is good enough?

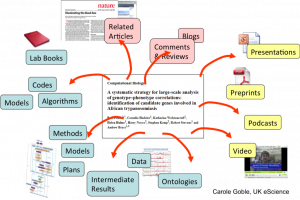

Computer science has tried to help, developing databases, analysis tools, email, wikis, even ontologies, along with ever-faster computers. But all these tools are distinct, none of them are connected. Certainly, they have helped make researchers more productive, but from a research communication perspective, they often make things worse, not better. They fragment the research content across a dozen separate applications.

eResearch (eScience in Europe, CyberInfrastructure in North America) has the bold aim of reinventing the research process as an integrated whole, so that it becomes more effective—easier to find what you need, to reuse what you find and even to refute the work of others.

So imagine, if you will, a better container for a piece of research than paper: an online resource where you can explore the actual tools, workflow and data used, where you can re-run the analysis for yourself to validate it, where the use of this piece of research is tracked automatically within its community, where it can be discovered and accessed via a web of connections among all of the above. Imagine a published experiment where one can click on a graph to download the data, click on an equation to examine the code, click on the code and re-run the analysis. Imagine too, that all these connections work both ways, so you can find all the methods that have been used on a dataset, or all the researchers who have validated an analysis.

So imagine, if you will, a better container for a piece of research than paper: an online resource where you can explore the actual tools, workflow and data used, where you can re-run the analysis for yourself to validate it, where the use of this piece of research is tracked automatically within its community, where it can be discovered and accessed via a web of connections among all of the above. Imagine a published experiment where one can click on a graph to download the data, click on an equation to examine the code, click on the code and re-run the analysis. Imagine too, that all these connections work both ways, so you can find all the methods that have been used on a dataset, or all the researchers who have validated an analysis.

Currently, we might count ourselves lucky if we can find relevant papers by using keywords, but have you tried finding relevant datasets or relevant methods? Our searching tends to be restricted by our familiarity with certain domains, by knowing the right keywords to use, by our social networks, even by the journals that the university library subscribes to: all these restrict our ability to find and reuse the research of others. For those 50 million articles to be really useful to us, they need to be re-factored. The same goes for code, data, workflows and all the research artefacts that we create.

eResearch will improve the way academic outcomes are communicated, archived, discovered, reused and valued. In doing so, perhaps we will also rid ourselves from the great plague of journal publishing houses that we have suffered from since 1665!