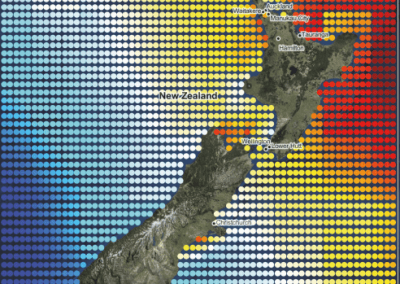

Asthma exacerbations in New Zealand 2010-2019: a national population-based study

Amy Hai Yan Chan1*, Andrew Tomlin1*, Kebede Beyene1,2, Jeff Harrison1 *Joint first authors 1School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2University of Health Sciences and Pharmacy, St Louis, Missouri

Asthma prevalence in NZ remains steady at ~10.3% with higher prevalence in Māori.

Total exacerbations increased by 33.4% in NZ between 2010 and 2019.

Exacerbation rates were highest among Māori and Pacific.

Hospital admissions for asthma decreased by 30.3% during the same period.

Over 50% of all admissions for asthma were experienced by Māori and Pacific patients.

Introduction

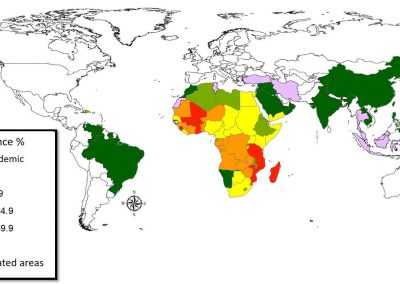

Data from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) consistently reports that New Zealand (NZ) has one of the highest rates of asthma symptoms in the world,1-3 and also a high prevalence of asthma, with one in five children and one in eight adults with asthma. There are also clear ethnic differences in the burden of asthma in NZ, with Māori and Pacific peoples being disproportionately affected.4 Asthma exacerbations represent the biggest contributor to burden of disease in people with asthma. Onset of asthma exacerbations can occur unexpectedly, leading to significant loss of quality of life for both the individual and their family, and are associated with loss of days at work and school. In rare cases, exacerbations can also lead to loss of life. Acute exacerbations and associated hospital visits place a significant burden on the health system, with the estimated costs of emergency department visits for asthma in NZ exceeding $120 million each year.5,6

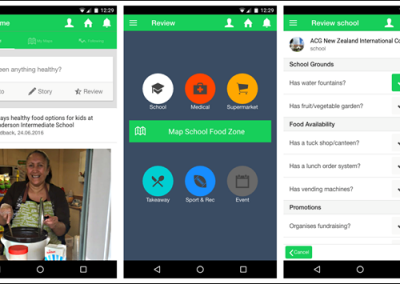

Despite the significant burden of asthma in NZ, there is a paucity of data on asthma exacerbation rates and how these have varied over time. This paper reports on a national population-based study of asthma exacerbation rates in NZ between 2010-2019, with an exploration of how these rates vary between different demographic groups such as people of different ages, sex and ethnicity. Specifically, the paper reports on asthma prevalence, severity, and medication use; asthma exacerbation rates, and hospital admissions for asthma.

Methods.

We conducted a retrospective population-based observational cohort study covering the ten years 2010-2019 to determine the prevalence of asthma and calculate asthma exacerbation and hospitalisation rates. Our study utilised de-identified data accessed from five national healthcare databases managed by NZ’s Ministry of Health. The study was approved by the Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee (AHREC), ethics number AH23069.

Data sources and patient population

NZ’s Ministry of Health maintains several national health databases. This study utilised data from the Primary Health Organisation (PHO) enrolment collection, the National Health Index (NHI) database, the National Minimum Dataset (NMDS), the Pharmaceutical Collection (Pharms), and the Mortality (MORT) register. The patient population and its sociodemographic characteristics were drawn from the PHO Enrolment Collection, which lists all patients registered with a primary care clinic (general practice) in NZ for each yearly quarter 2010-2019, and the NHI database which records details on all patients who have accessed NZ’s healthcare system. Patients were grouped into five age categories (<5, 5-14, 15-44, 45-64, and >=65 years).7-9 For ethnicity, patient prioritised ethnicity was used.10,11 Socioeconomic deprivation status was based on NZ’s socioeconomic index of deprivation which was derived following national censuses conducted in 2006, 2013 and 2018.12,13 Deprivation status was grouped into five quintiles (1 – least deprived; 5 – most deprived). We excluded patients if their recorded age or sex was not consistently recorded in the national datasets. Hospital admissions for asthma were identified from the NMDS which contains data on all publicly funded inpatient and day case discharges from NZ public hospitals and private hospitals. Hospital diagnoses in the NMDS are coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM). For information on medication use, dispensed medication records for included patients were accessed from the Pharmaceutical Collection (Pharms) which records detailed information on all nationally subsidised medicines dispensed from NZ community pharmacies. Pharmaceuticals were classified by the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system.14 Information on death dates was obtained from the Mortality (MORT) dataset. Patient records from the national databases were linked using each patient’s unique encrypted NHI (National Health Index) code.

Asthma cohorts

Patients with asthma were included in yearly cohorts if they had been admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of asthma (ICD-10-AM: J45 or J46), or had been dispensed any asthma medication during the year. Subsidised asthma medications were identified from the NZ Formulary15. Patients with any diagnosis of chronic lung disease (ICD-10-AM: J40-44) or use of the pharmaceuticals salbutamol with ipratropium, tiotropium, glycopyrronium, or umeclidinium were excluded from the asthma cohort of a particular year, and all subsequent years.

Asthma exacerbations

An asthma exacerbation was defined as a primary discharge diagnosis of asthma (ICD-10-AM: J45 or J46) from an hospital admission, or a course of oral corticosteroids (OCS), dispensed at least seven days since any previous dispensing of OCS. OCS medications included prednisone, prednisolone and methylprednisolone and dexamethasone tablets.

Asthma hospitalisations

Patients admitted to hospital with asthma were identified based on an ICD-10-AM diagnostic code of J45 or J46 from the NMDS.

Statistical analysis

The annual prevalence of asthma was estimated for all patients combined and within each age group, ethnic group, deprivation quintile, and by sex, using the total number of patients enrolled in primary care in each calendar year as the denominator. Enrolled patients are recorded in the PHO dataset which covers approximately 98% of the New Zealand population. Annual asthma exacerbation rates were calculated as the number of exacerbations per 1,000 patient-years where the number of days at risk for each patient in each year was the number of calendar days in the year, or the number of days since birth or before death during the year, as appropriate. Acute hospital admission rates for asthma were also calculated, as were the proportions of patients admitted to hospital with a primary diagnosis of asthma. We categorised each asthma patient in each year within one of four asthma severity steps based on their dispensed asthma medications, and quantified exacerbation rates by severity step.16-18 Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) between 2010 and 2019 were estimated for asthma exacerbations and asthma hospitalisations for all patients combined, and for each sociodemographic patient group using Poisson regression adjusting for age, sex, and deprivation as appropriate. Adjusted IRR were also calculated for asthma exacerbations by asthma severity step. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Asthma prevalence

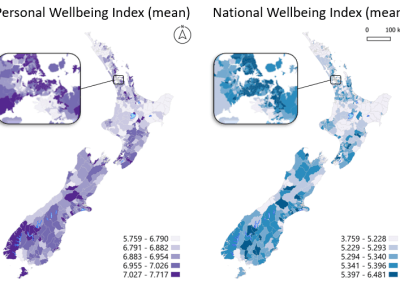

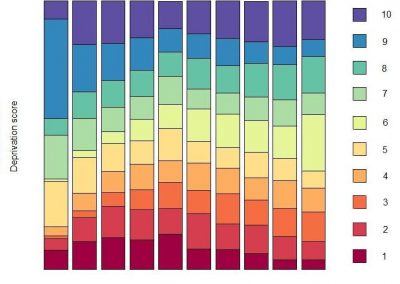

The estimated prevalence of asthma was 10.3% in both 2010 and 2019 with the total number of patients with asthma increasing from 447,797 to 512,627. Prevalence of asthma was higher for females than males in all years (Figure 1a), and higher for children under the age of five years than in other age groups (Figure 1b). In 2010 and 2019, asthma prevalence in Māori patients was 13.1% and 12.9% respectively, for Pacific patients 10.4% and 11.0%, and for European patients 10.1% and 10.3% (Figure 1c). Prevalence also increased with increasing socioeconomic deprivation status (Figure 1d). In 2010 and 2019, asthma prevalence was 9.2% and 9.8% for patients residing in the least deprived areas (quintile 1), and 10.2% and 11.1% for patients living in the most deprived areas (quintile 5).

Asthma exacerbations

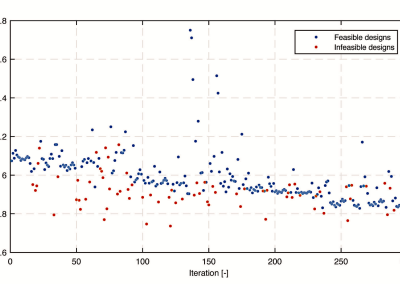

The overall rate of asthma exacerbations increased significantly from 376.2 per 1,000 patient-years in 2010 to 438.3 in 2019 based on hospital discharge diagnosis data and OCS dispensing data. Of these, 98.8% of all asthma exacerbations across the ten-year period were identified from courses of OCS dispensed in the outpatient setting. The total number of OCS courses dispensed increased by 63.2% from 244,865 OCS courses dispensed in 2010 to 399,661 OCS courses in 2019. The number of patients with asthma dispensed these OCS courses increased by 72.5% from 119,524 patients in 2010 (26.7% of all patients with asthma in 2010) to 206,155 patients in 2019 (40.2% of all patients with asthma in 2019).

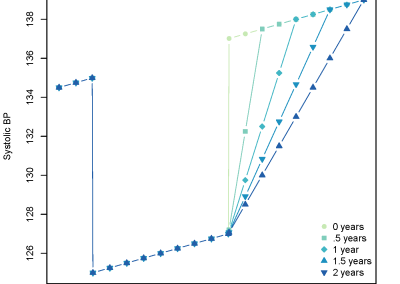

Hospital admissions for asthma

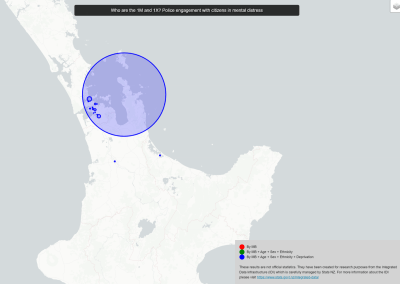

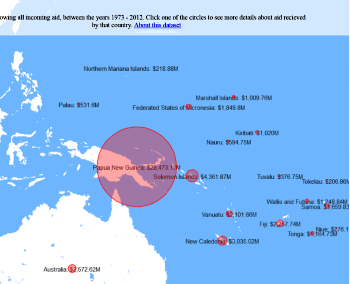

The total number of hospital admissions for asthma decreased significantly between 2010 and 2019, with the admission rate over 25% lower in 2019 than 2010 after adjusting for changes in the demographic profile of NZ’s primary care population. Figure 3 shows the number of patients admitted for asthma compared to the total number of asthma admissions, indicating that a small but significant proportion of patients are readmitted each year. Overall, acute admissions for asthma decreased by 30.3% between 2010 to 2019, from 15.2% of patients in 2010 to 13.7% in 2019 admitted for asthma more than once. Over 50% of all NZ admissions for asthma were experienced by Māori and Pacific asthma patients in both 2010 and 2019 despite these two ethnic groups comprising only 25% of the total asthma population in these years. Total admissions for asthma were over three times higher for the most socioeconomically deprived asthma patients than those least deprived in both 2010 and 2019.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to provide a descriptive analysis of asthma exacerbations experienced by patients with asthma in NZ and the trends in exacerbation rates over a ten-year period between 2010-2019. It provides a summary of the changes in estimated prevalence of asthma in NZ by ethnicity, age, sex and deprivation during this decade, and rates of acute hospital admissions for asthma. Our study found that asthma prevalence was largely unchanged between 2010 and 2019, with differences by sex and age similar to that reported in other studies19,20. In terms of exacerbation rates, our study found a significant increase in exacerbations over time, with higher rates in the very young and older age groups, and with increasing severity of asthma. These findings concur with other international studies of asthma exacerbations despite differences in the data available for analysis and the criteria used to define asthma exacerbations. NZ has a similar health system to countries that have universal health coverage such as the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, and Australia and our findings may be applicable to countries with universal health coverage. Of concern is the high exacerbation rates that continue to be observed in Māori and Pacific communities, which represent priority groups for improving asthma care and management, though hospitalisation rates have reduced for both groups. Unexpectedly, the greatest increase in exacerbations was found in the least deprived patients with the smallest increase occurring in those most deprived. This contrasts with most of the literature which show increased exacerbation rates in patients with greater socioeconomic deprivation21. However, as we used OCS dispensing as a proxy indicator for exacerbations, the observed increase in exacerbation may be driven by higher OCS prescribing and / or greater healthcare contact in those who are less deprived rather than indicating worse asthma control per se. There is likely to be a correlation between deprivation status and ethnicity, as seen with the deprivation gradient in mortality by ethnicity22, as social determinants of health including income and deprivation are not equally distributed across ethnicities23. This could partially explain the exacerbation differences by deprivation and ethnicity seen. As access to hospitals is free in NZ, but access to primary care is not, there could be differences in health-seeking behaviours for asthma exacerbations which could explain the differences seen across sociodemographic groups. As our study is informed by data from national health datasets, we are unable to identify exact reasons for the differences observed. In-depth qualitative research is needed to fully identify factors driving differences in exacerbation rates by ethnicity and deprivation status, and to determine whether there has indeed been a change in disease pattern over time or if the data indicate a change in prescriber behaviour in response to patient presentations. Interestingly, whilst total exacerbations increased by 33.4% (increasing from 167,987 asthma exacerbations in 2010 to 224,050 in 2019), hospital admissions for asthma decreased by 30.3% during the same period.

Our study has limitations as NZ has no national primary care dataset, so data on asthma exacerbations and hospitalisations come from hospital discharge diagnoses and from pharmaceutical dispensing data. Similar to other pharmacoepidemiology studies, the calculated rates can be affected by the definitions of asthma and exacerbations used.

Whilst our study examined exacerbation and hospitalisation rates in several sociodemographic groups, our analyses were only limited to data available in the national datasets. Several other factors that may affect exacerbation and hospitalisation rates such as patient comorbidities, medication adherence, health and treatment beliefs were not explored, and would be the subject of future research.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to describe the trends in asthma prevalence, exacerbation and hospitalisation rates in NZ over a ten-year period from 2010-2019. Our findings highlight increasing exacerbations in NZ with a corresponding reduction in hospitalisation rates for asthma. This may reflect a change in how asthma is managed between primary and secondary care, and provides important information for health professionals and policymakers to consider when planning asthma care. The higher exacerbation rates observed in certain sociodemographic groups warrants further investigation to determine if there are modifiable factors, such as differences in exacerbation management, that are leading to the differences in exacerbation rates being observed in different sociodemographic groups in NZ.

- Asher M, Keil U, Anderson H, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):483-491.

- Lai C, Beasley R, Crane J, Foliaki S, Shah J, Weiland S, ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: Phase Three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax. 2009;64:476-483.

- Pearce N, Sunyer J, Cheng S, Chinn S, Björkstén B, Burr M, et al. Comparison of asthma prevalence in the ISAAC and the ECRHS. 2000;16(3):420-426.

- Pattemore PK, Ellison-Loschmann L, Asher MI, Barry DM, Clayton TO, Crane J, et al. Asthma prevalence in European, Maori, and Pacific children in New Zealand: ISAAC study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37(5):433-442.

- Barnard LT, Zhang J. The impact of respiratory disease in New Zealand: 2020 update. In. Wellington: Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ; 2021.

- Telfar Barnard L, Zhang J. The impact of respiratory disease in New Zealand: 2018 update. Asthma Respiratory Foundation NZ; 2018.

- American Lung Association. Asthma trends and burden. 2022; https://www.lung.org/research/trends-in-lung-disease/asthma-trends-brief/trends-and-burden Accessed 22 July, 2022.

- Bloom CI, Nissen F, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L, Cullinan P, Quint JKJT. Exacerbation risk and characterisation of the UK’s asthma population from infants to old age. 2018;73(4):313-320.

- Selroos O, Kupczyk M, Kuna P, Łacwik P, Bousquet J, Brennan D, et al. National and regional asthma programmes in Europe. 2015;24(137):474-483.

- Boven N, Exeter D, Sporle A, Shackleton N. The implications of different ethnicity categorisation methods for understanding outcomes and developing policy in New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 2020;15(1):123-139.

- Health Mo. Ethnicity data protocols for the health and disability sector. In. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2004.

- Atkinson J, Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep2013 index of deprivation. In. Wellington: Department of Public Health, University of Otago; 2014.

- Salmond CE, Crampton PJCjophRCdsep. Development of New Zealand’s deprivation index (NZDep) and its uptake as a national policy tool. 2012:S7-S11.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013. In. Oslo: WHO; 2012.

- New Zealand Formulary. New Zealand Formulary version 127. In. New Zealand: NZF; 2023.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Fontana (US)2019.

- Beasley R, Beckert L, Fingleton J, Hancox RJ, Harwood M, Hurst M, et al. Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ Adolescent and Adult Asthma Guidelines 2020. 2020.

- Chipps BE, Murphy KR, Oppenheimer JJTJoA, Practice CII. 2020 NAEPP Guidelines Update and GINA 2021—asthma care differences, overlap, and challenges. 2022;10(1):S19-S30.

- Asher MI, García-Marcos L, Pearce NE, Strachan DP. Trends in worldwide asthma prevalence. 2020;56(6):2002094.

- Lundbäck B, Backman H, Lötvall J, Rönmark E. Is asthma prevalence still increasing? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10(1):39-51.

- Redmond C, Akinoso-Imran AQ, Heaney LG, Sheikh A, Kee F, Busby J. Socioeconomic disparities in asthma health care utilization, exacerbations, and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2022;149(5):1617-1627.

- Tobias M, Yeh L-C. Do all ethnic groups in New Zealand exhibit socio-economic mortality gradients? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30(4):343-349.

- Bécares L, Cormack D, Harris R. Ethnic density and area deprivation: Neighbourhood effects on Māori health and racial discrimination in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;88:76-82.

See more case study projects

Our Voices: using innovative techniques to collect, analyse and amplify the lived experiences of young people in Aotearoa

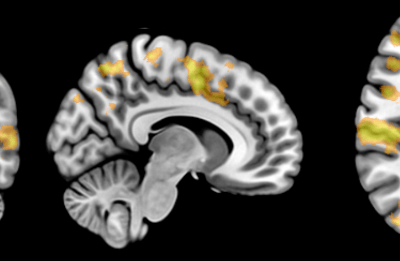

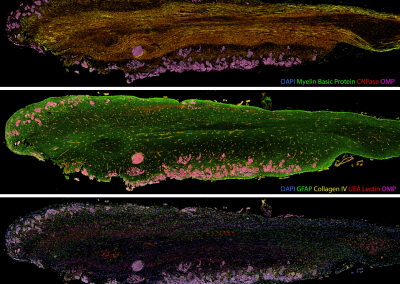

Painting the brain: multiplexed tissue labelling of human brain tissue to facilitate discoveries in neuroanatomy

Detecting anomalous matches in professional sports: a novel approach using advanced anomaly detection techniques

Benefits of linking routine medical records to the GUiNZ longitudinal birth cohort: Childhood injury predictors

Using a virtual machine-based machine learning algorithm to obtain comprehensive behavioural information in an in vivo Alzheimer’s disease model

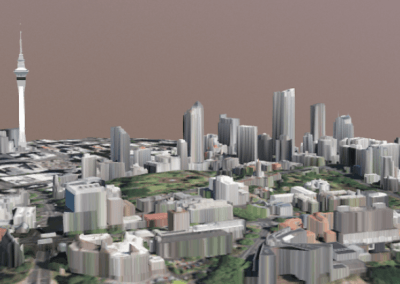

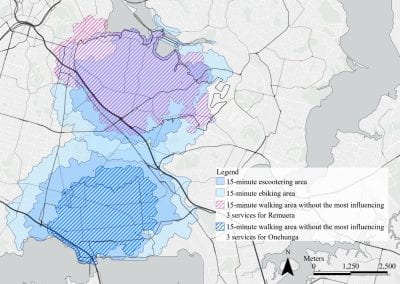

Mapping livability: the “15-minute city” concept for car-dependent districts in Auckland, New Zealand

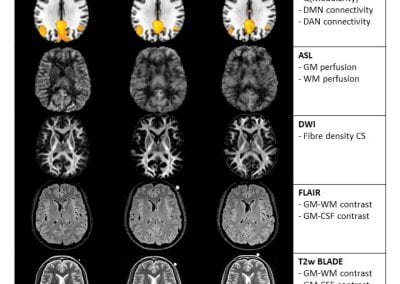

Travelling Heads – Measuring Reproducibility and Repeatability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Dementia

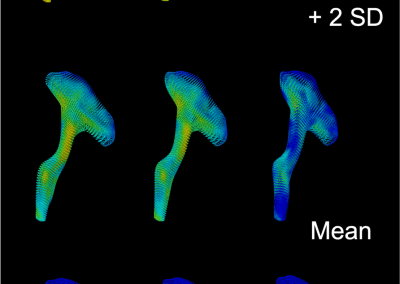

Novel Subject-Specific Method of Visualising Group Differences from Multiple DTI Metrics without Averaging

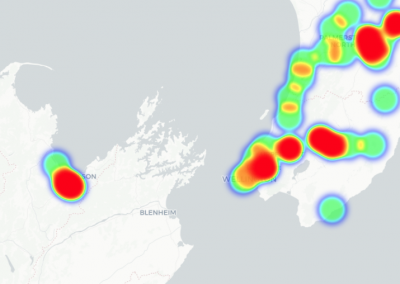

Re-assess urban spaces under COVID-19 impact: sensing Auckland social ‘hotspots’ with mobile location data

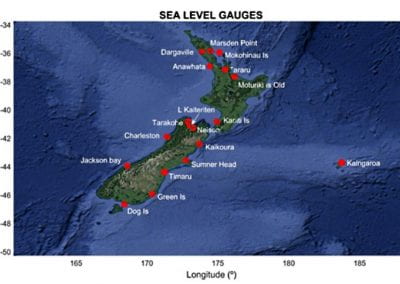

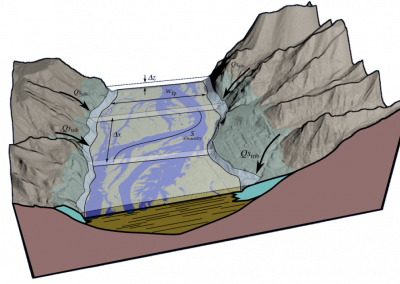

Aotearoa New Zealand’s changing coastline – Resilience to Nature’s Challenges (National Science Challenge)

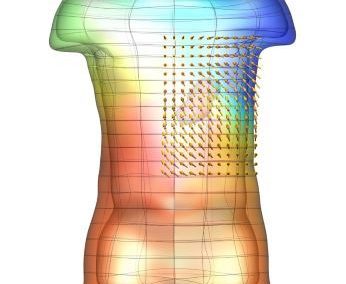

Proteins under a computational microscope: designing in-silico strategies to understand and develop molecular functionalities in Life Sciences and Engineering

Coastal image classification and nalysis based on convolutional neural betworks and pattern recognition

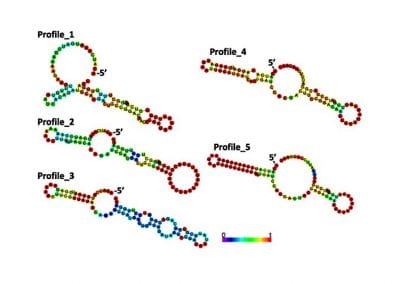

Determinants of translation efficiency in the evolutionarily-divergent protist Trichomonas vaginalis

Measuring impact of entrepreneurship activities on students’ mindset, capabilities and entrepreneurial intentions

Using Zebra Finch data and deep learning classification to identify individual bird calls from audio recordings

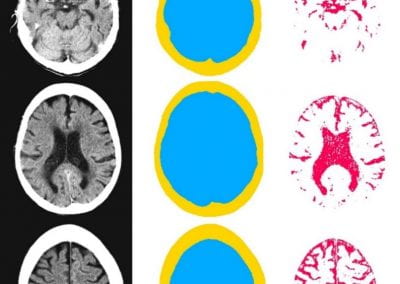

Automated measurement of intracranial cerebrospinal fluid volume and outcome after endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke

Using simple models to explore complex dynamics: A case study of macomona liliana (wedge-shell) and nutrient variations

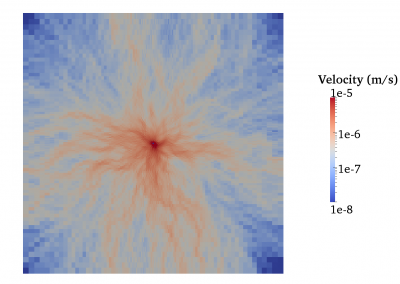

Fully coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modelling of permeability enhancement by the finite element method

Modelling dual reflux pressure swing adsorption (DR-PSA) units for gas separation in natural gas processing

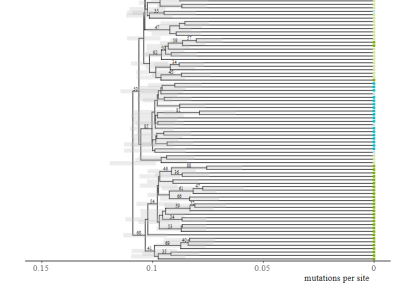

Molecular phylogenetics uses genetic data to reconstruct the evolutionary history of individuals, populations or species

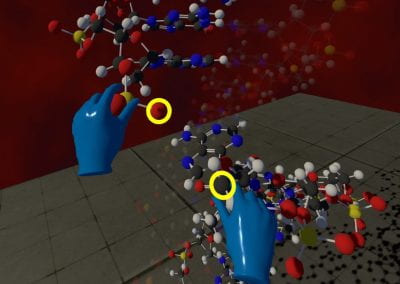

Wandering around the molecular landscape: embracing virtual reality as a research showcasing outreach and teaching tool