The impact of upzoning on housing construction in Auckland

Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy a, Peter C.B. Phillips a b c d

a The University of Auckland

b. Yale University, United States

c. Singapore Management University, Singapore

d. University of Southampton, United Kingdom

Introduction

Housing has become prohibitively expensive in many of the world’s major cities, precipitating serious and widespread housing affordability crises (Wetzstein, 2017). A growing coalition of researchers argue that part of the solution is to “upzone” cities by relaxing land use regulations (LURs) to allow construction of more intensive housing, such as townhouses, terrace housing and apartment buildings (Glaeser, Gyourko, 2003, Freeman, Schuetz, 2017, Manville, Monkkonen, Lens, 2019). Policymakers have begun to listen to these supply-side solutions and, in response, several metropolitan and gubernatorial authorities have pursued zoning reform in recent years (National Public Radio, 2019).

There is a growing debate about whether upzoning is an effective policy response to housing shortages and unaffordable housing. This paper provides empirical evidence to further inform debate by examining the various impacts of recently implemented zoning reforms on housing construction in Auckland, the largest metropolitan area in New Zealand. In 2016, the city upzoned approximately three quarters of its residential land to facilitate construction of more intensive housing. We use a quasi-experimental approach to analyze the short-run impacts of the reform on construction, allowing for potential shifts in construction from non-upzoned to upzoned areas (displacement effects) that would, if unaccounted for, lead to an overestimation of treatment effects. We find strong evidence that upzoning stimulated construction. Treatment effects remain statistically significant even under implausibly large displacement effects that would necessitate more than a four-fold increase in the trend rate of construction in control areas under the counterfactual of no-upzoning. Our findings support the argument that upzoning can stimulate housing supply and suggest that further work to identify factors that mediate the efficacy of upzoning in achieving wider objectives of the policy would assist policymakers in the design of zoning reforms in the future.

Institutional background

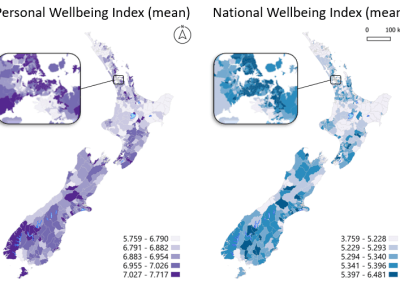

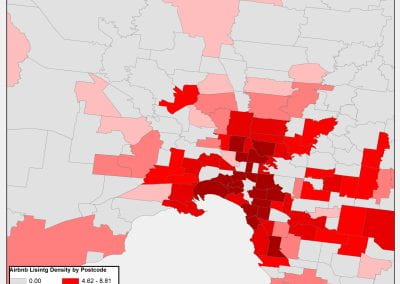

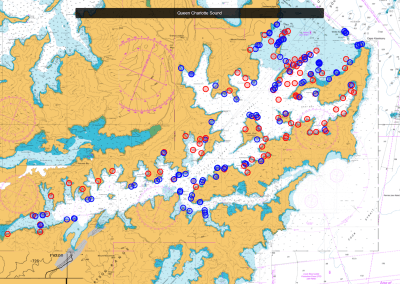

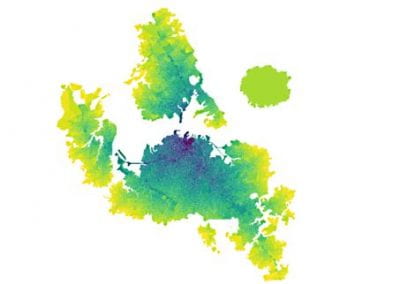

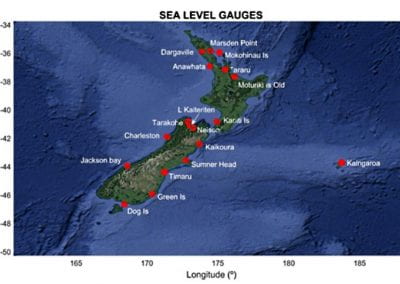

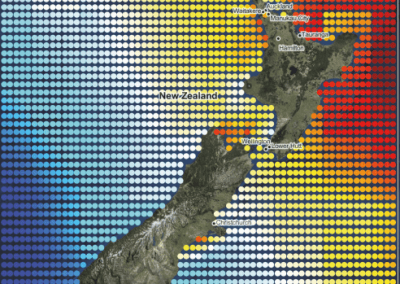

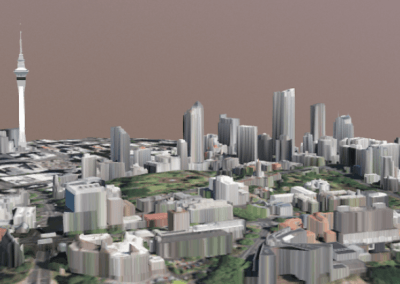

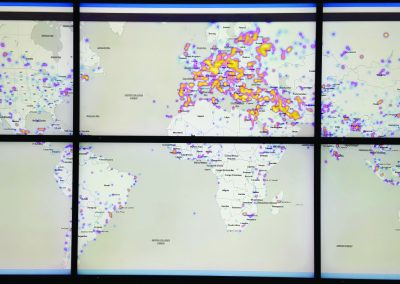

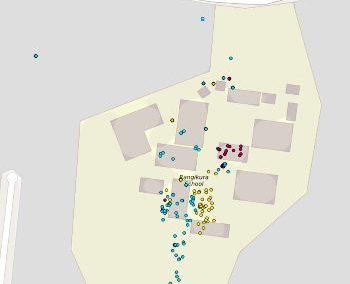

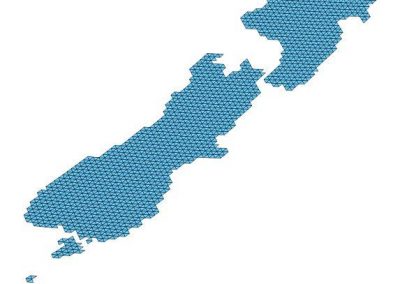

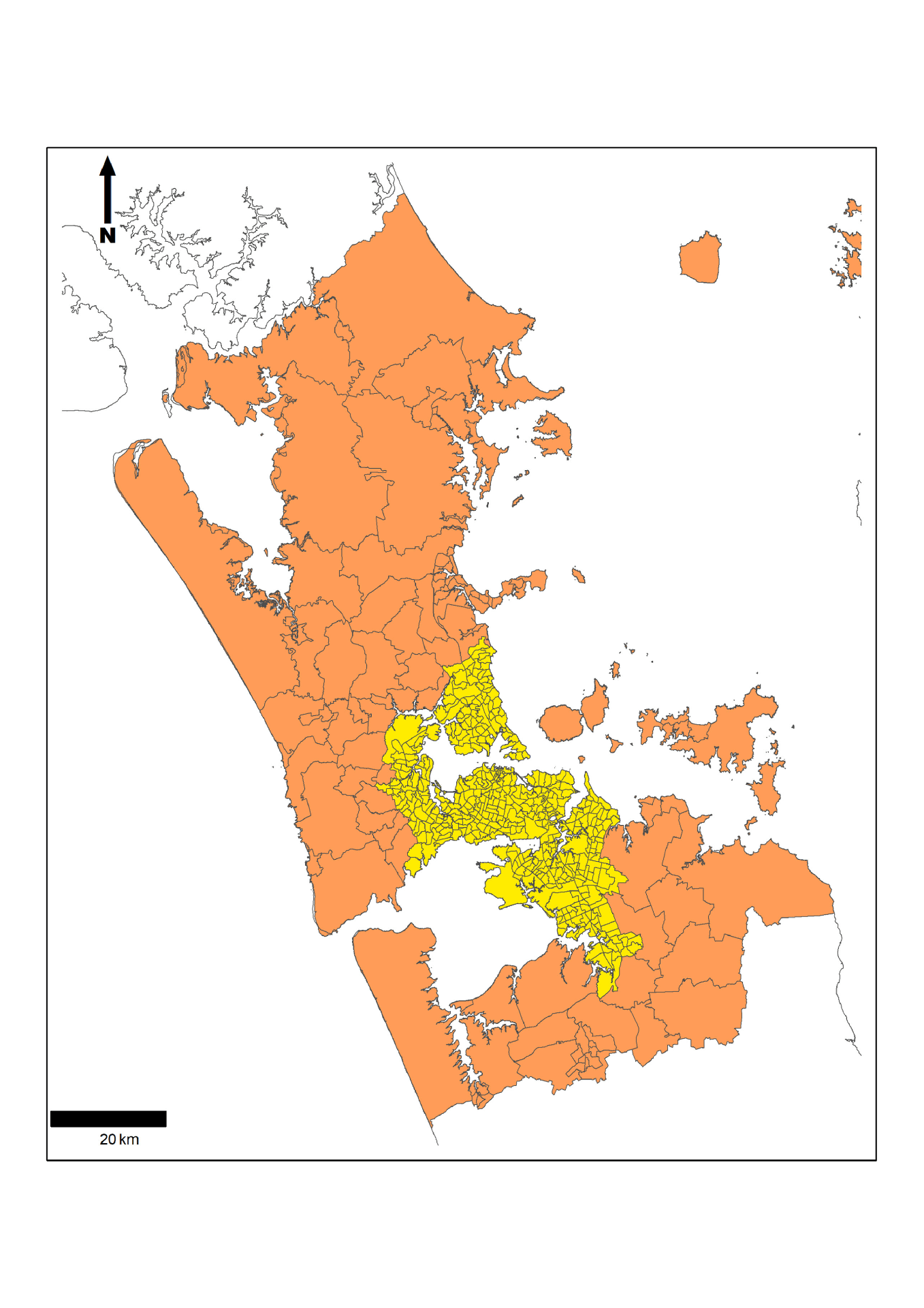

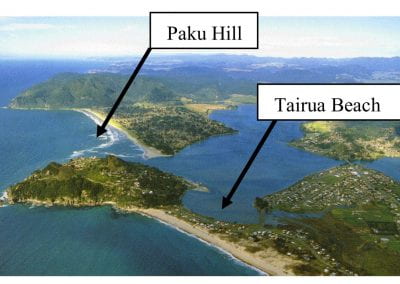

Auckland with a population of approximately 1.57 million within the greater metropolitan region (as of the 2018 census). Prior to 2010, the metropolitan region comprised seven different city and district councils. Since 2010, the entire metropolitan area, as well as several towns, populated islands, and a large amount of the rural land beyond the fringes of its outermost suburbs, has been under the jurisdiction of a single local government, the Auckland Council. Centered on a long isthmus of land between two harbors, this jurisdiction extends over 4894 km 2 of land area. Figure 1 illustrates the Auckland region, decomposed into Statistical Areas (SAs), which, as discussed below, are used as the geographic unit of analysis in our work. The shaded areas are the Auckland Council region. The lighter shaded area in the center is what we refer to as the “urban core”. 1 In March 2013, the Auckland Council announced the “draft” version of the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP). The draft version of the plan went through several rounds of consultations, reviews and revisions before the final version became operational on 15 November 2016.

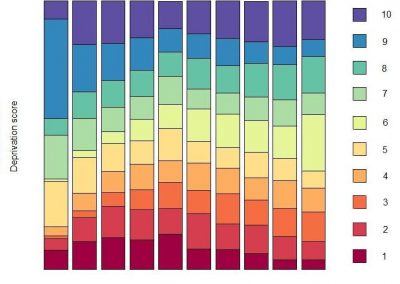

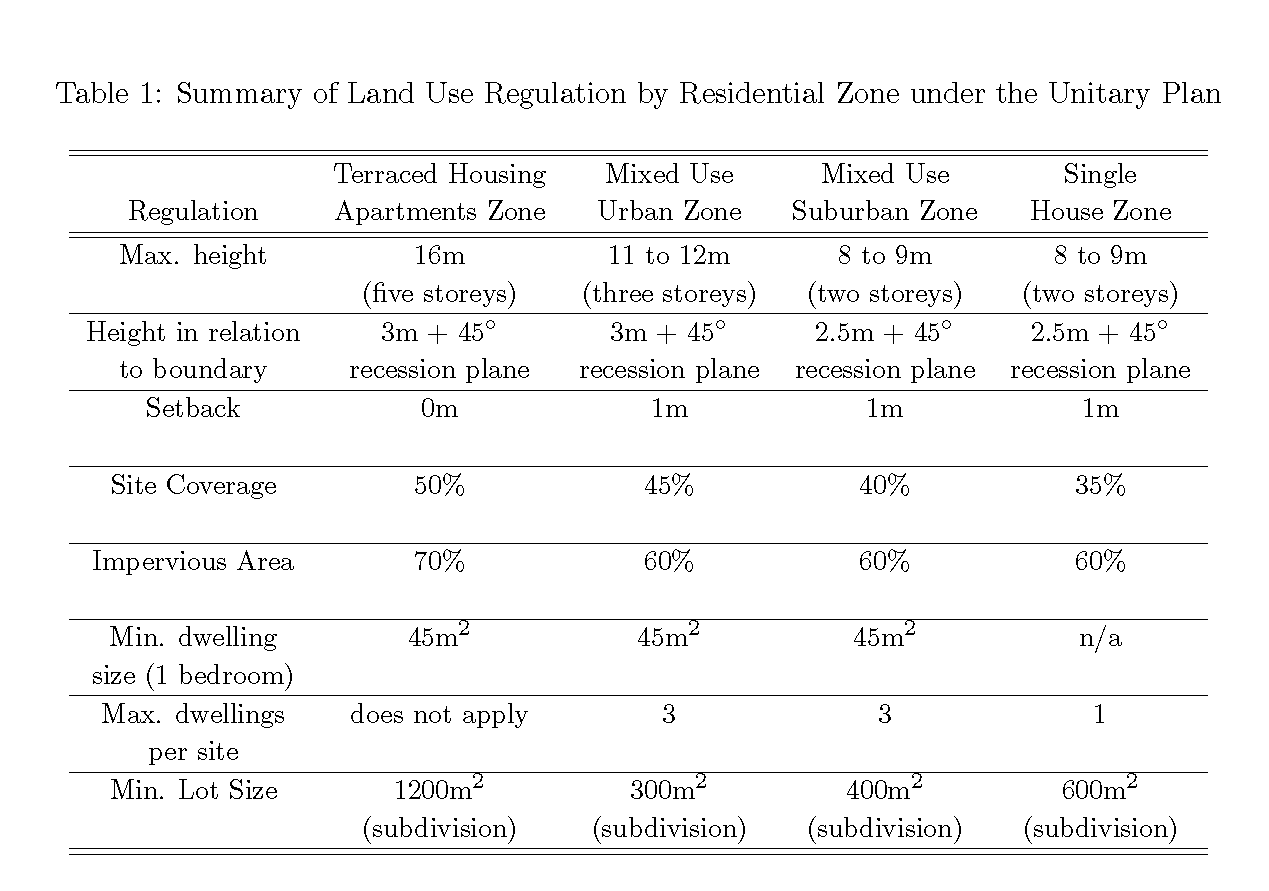

In this study we focus on four residential zones introduced under the AUP, listed in declining levels of permissible site development: Terrace Housing and Apartments (THA); Mixed Housing Urban (MHU); Mixed Housing Suburban (MHS); and Single House (SH). Thus THA allows the most site development, and SH allows the least. Table 1 summarizes the various LURs for each of the four residential zones considered. These regulations include site coverage ratios, height restrictions, setbacks and building envelopes, among others.2

Annotate:

1. For the urban core, we use statistical areas inside or overlapping the “Major Urban Area ”of the greater metropoitan region, as defined by Statistics New Zealand.

2 There are two additional zones in the AUP that are classified as “Residential”: “Large Lot ”and “Rural and Coastal Settlement ”. We exclude these areas from our analysis as they are an intermediate, semi-rural zone between outright rural and urban housing areas. We also omit residential land on the islands in the Hauraki Gulf, which have their own unique zoning under the AUP.

Figure 1. Auckland region.

Notes: Auckland region (shaded) decomposed into Statistical Area geographic units. Urban core shaded yellow in the center. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Notes: Tabulated restrictions are “as of right ”and can be exceeded through resource consent notification. Number of storeys (in parentheses) are obtained from the stated purpose of the height restriction in the regulations. Height in relation to boundary and setbacks apply to side and rear boundaries. Less restrictive height in relation to boundary rules than those tabulated apply to side and rear boundaries within 20m of site frontage. Maximum dwellings per site are the number allowed as of right. Minimum lot sizes per dwelling do not apply to existing residential parcels. Site coverage is the area under the dwelling structure. Impervious area is the area under the dwelling and structures such as concrete driveways that prevent rainwater absorption into soil.

Dataset

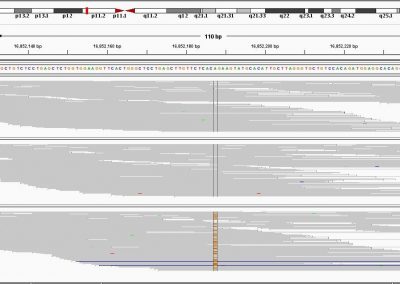

Our dataset is based on annual building permits for new dwelling units issued by the Auckland Council from 2010 to 2021.6 The permits include the number of dwellings. Each observation includes the longitude and latitude of the building site, which have been used to map each permit to its corresponding zone under the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP).

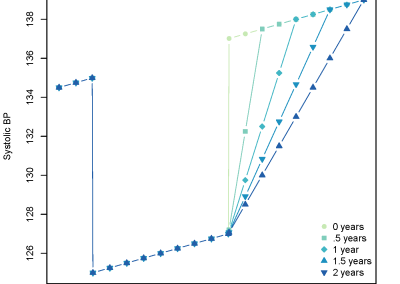

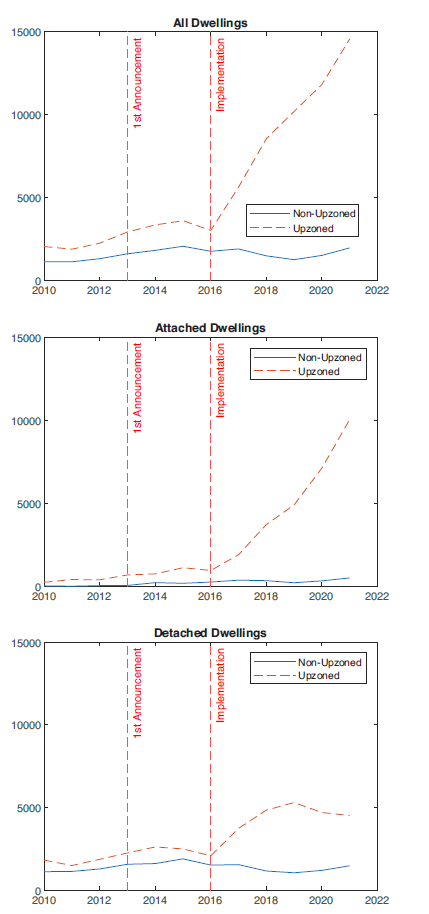

Figure 2 exhibits aggregate permits in upzoned and non-upzoned residential areas over the 2010 to 2021 period. We also decompose permits into attached and detached dwellings. There is a clear increase in the number of permits in upzoned areas after the policy is implemented (from 2017 onward). The number of attached dwelling permits per year in upzoned areas increases from under 1000 in 2016 to near 10,000 by 2021 –more than a tenfold increase. Over the same period, detached housing increases from just over 2000 permits per year to approximately 4500. By 2019, there were more attached dwelling permits than detached, consistent with the upzoning goal of incentivising more capital intensive structures. In addition, there is a notable fall in detached dwelling permits between 2019 and 2021 in upzoned areas.

Prior to the policy change, permits in subsequently upzoned areas consistently exceeded permits in non-upzoned areas by a relatively constant amount. This pattern is consistent with modeling permits in levels in a difference-in-differences framework, since it implies an absolute difference in the level of the two series under the counterfactual (Kahn-Lang and Lang, 2020 ).

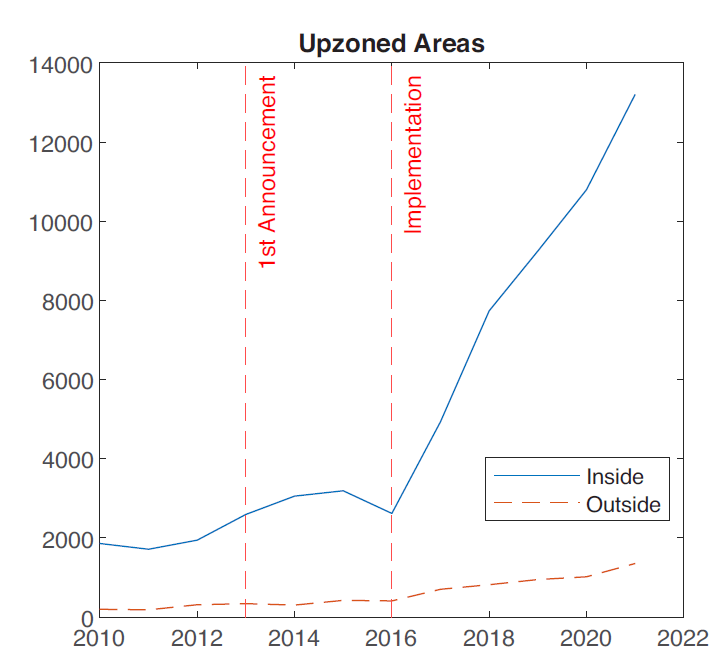

Economic theories of urban development suggest that upzoning will encourage construction in desirable locations where zoning regulation was previously binding, such as areas close to job locations. The canonical Alonso-Muth-Mills (AMM) spatial equilibrium model of the mono- centric city predicts that a relaxation of Land Use Regulations (LURs) will result in more housing close to the city to the center ( Bertaud and Brueckner, 2005 ). To explore whether this is the case in Auckland, Figure 3 (a.b.) divides the sample into urban core and non-core areas of Auckland (see Figure 1 for the geographic delineation of the urban core and non-core areas). Consistent with this prediction, most of the increase in permits in upzoned areas is occurring in the urban core. Figure 4 breaks down the upzoned areas into constituent Terrace Housing and Apartments (THA), Mixed Housing Urban, (MHU) and Mixed Housing Suburban (MHS) zones. Despite having more restrictive constraints than MHU and THA, it is unsurprising that MHS accounts for most of the increase in permits because it covers the largest geographic area.

Empirical model and result

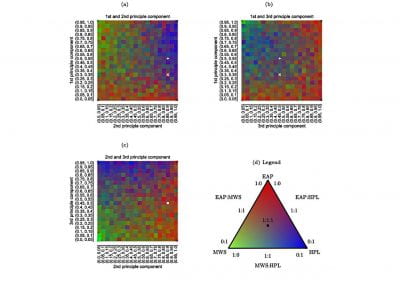

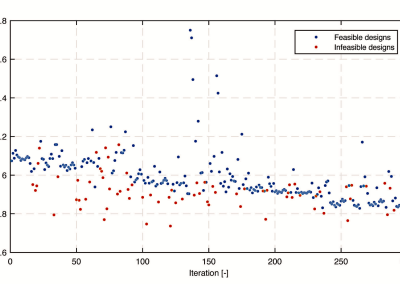

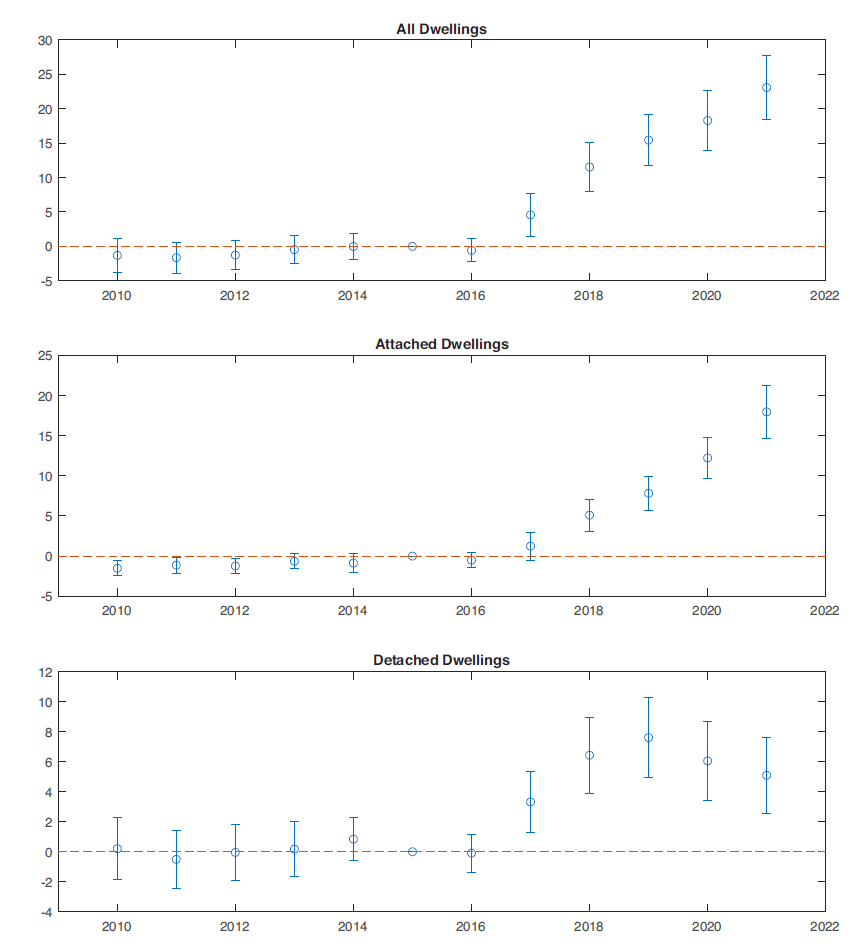

Figure 5 shows OLS estimates of the coefficients alongside 95% confidence intervals (standard errors are clustered by SA). Recall that we set the treatment to occur in 2015. The top panel of the Figure displays results for all dwellings, while the middle and bottom panels display results for detached and attached dwellings, respectively. Evidently there is no apparent trend in the estimated coefficients prior to treatment in any of the three samples, so the parallel trends assumption appears to hold. Further buttressing the DID framework, we find no evidence of anticipation in land prices or sales volumes prior to policy announcement, nor selection into treatment based on specifications that admit neighborhood-specific trends. The response to the zoning change is immediate: The estimated treatment effects increase every year after implementation. By 2021, five years after the policy was introduced, some 23.06 additional permits are issued, on average, in upzoned areas compared to non-upzoned areas in each of the 479 SAs. This would correspond to 11,044 permits across the city. Cumulating the corresponding figures for 2016 through 2021 yields 34,614 additional permits in upzoned areas compared to non-upzoned areas. Treatment effects for attached dwellings exceed detached from 2019 onwards. By 2021, the estimated treatment effect for attached is 17.96 permits, while for detached it is 5.09. The original paper was published in Journal of Urvan Economics, For detailed analysis and model equations, please refer to the original paper https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2023.103555.

Discussion

The empirical findings show strong evidence to support the conclusion that upzoning raised dwelling construction in the city of Auckland. Set-identified treatment effects remain statistically significant even under counterfactual sets that include an implausibly large, four-fold increase in the trend rate of construction in control areas under the counterfactual of no-upzoning. The data also reveal that much of this increase is in the form of the more capital intensive, attached (or multifamily) structures in the inner suburbs of the city. These findings are a positive sign for proponents of upzoning as a solution to unresponsive housing supply, particularly when compared to recent studies that show that zoning reforms have not had a substantial impact on housing construction ( Freemark, 2019; Limb and Murray, 2022 ). Although the present paper does not explicitly identify factors that mediate the efficacy of zoning reforms in different contexts, comparisons to other reforms may shed light on the underlying mechanisms and thereby assist in directing future research. For example, the large-scale upzoning in Auckland may have fostered greater competition in land supply to developers, resulting in lower upzoned land prices than would have occurred if the policy had instead been restricted to specific neighborhoods or transit corridors. Alternatively, demand for housing in Auckland has significantly outstripped supply over the past few decades, resulting in housing that is amongst the most expensive in the world when measured against local incomes: Auckland may have significantly more latent demand for housing than other cities. We anticipate future research will address these questions to further guide policymakers in the design and implementation of zoning reforms. We conclude by noting that the impact of upzoning on housing construction and housing markets will continue to be felt over coming years. Permits for attached dwellings are still trending upwards and permits for detached dwellings remain significantly above their pre-upzoning average. In future work, and as new data become available, the impact of the policy on the housing stock will be updated and new research will seek to determine the particular characteristics of parcels that predict the uptake of redevelopment. Such findings should be useful in assisting the design and refinement of future upzoning policies.

Annotate:

3. FARs are often used as a measure of LUR stringency; see Brueckner et al. (2017) ; Brueckner and Singh (2020) and Tan et al. (2020) . By using a FAR, our upzoning identification algorithm is based on increases in maximum floorspace density, rather than restrictions on dwelling density, such as minimum lot sizes (MLS). While the majority of the zones prior to the AUP also had MLS in addition to height and site coverage restrictions, MLS do not apply to extant residential parcels under the AUP. MLS on extant parcels were therefore an additional restriction that only applied prior to the AUP, which means that our upzoning classification method may understate the amount of upzoned land.

4 We also consider empirical designs in which THA, MHU and MHS are simply classified as the treatment group and SH areas are the control group, and where downzoned areas are excluded from the analysis. Our results and findings do not substantively change.

5. Loan to value ratios on new residential mortgages were introduced in 2013; a limited capital gains tax was introduced in 2015; and legislation preventing foreign ownership (excepting Australia and Singapore) in 2018. See Greenaway- McGrevy and Phillips (2021) for additional details.

6.Permits for extensions to existing dwellings are not included in our analysis.

- Bertaud, A., Brueckner, J.K., 2005. Analyzing building-height restrictions: predicted impacts and welfare costs. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 35 (2), 109–125. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2004.02.004 .

- Brueckner, J.K., Fu, S., Gu, Y., Zhang, J., 2017. Measuring the stringency of land use regulation: the case of China’s building height limits. Rev. Econ. Stat. 99 (4), 663–677. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00650 .

- Brueckner, J.K., Singh, R., 2020. Stringency of land-use regulation: building heights in US cities. J. Urban Econ. 116 (January), 103239. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2020.103239 .

- Freeman, L., Schuetz, J., 2017. Producing affordable housing in rising markets: What works? Cityscape 19, 217–236.

- Freemark, Y., 2019. Upzoning chicago: impacts of a zoning reform on property

values and housing construction:. Urban Aff. Rev. 56 (3), 758–789.doi:10.1177/1078087418824672. - Kahn-Lang, A., Lang, K., 2020. The promise and pitfalls of differences-in-differences: reflections on 16 and pregnant and other applications. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 38 (3), 613–620. doi: 10.1080/07350015.2018.1546591.

- Glaeser, E., Gyourko, J., 2003. The impact of building restrictions on housing affordability. Econ. Policy Rev. 9 (2), 21–39 .

- Greenaway-McGrevy, R., Phillips, P.C.B., 2021. House prices and affordability. New Zealand Econ. Pap. 55 (1), 1–6. doi:10.1080/00779954.2021.1878328.

- Limb, M., Murray, C.K., 2022. We zoned for density and got higher house

prices: supply and price effects of upzoning over 20 years. Urban Policy Res.doi:10.1080/08111146.2022.2124966. https://www.osf.io/zkt7v/. - Manville, M., Monkkonen, P., Lens, M., 2019. It’s time to end single-family zoning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 86 (1), 106–112. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2019.1651216.

- National Public Radio, 2019. Across America: How U.S. Cities Are Tackling The Affordable Housing Crisis. https://www.npr.org/2019/08/28/755113175/1a-across-america-how-u-s-cities-are-tackling-the-affordable-housing-crisis .

- Tan, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, Q., 2020. Land-use regulation and the intensive

margin of housing supply. J. Urban Econ. 115 (October 2019), 103199.

doi:10.1016/j.jue.2019.103199 . - Wetzstein, S., 2017. The global urban housing affordability crisis. Urban Stud. 54 (14),3159–3177. doi:10.1177/0042098017711649.

See more case study projects

Our Voices: using innovative techniques to collect, analyse and amplify the lived experiences of young people in Aotearoa

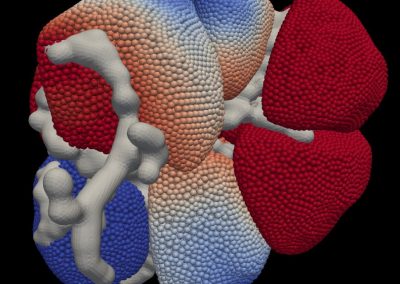

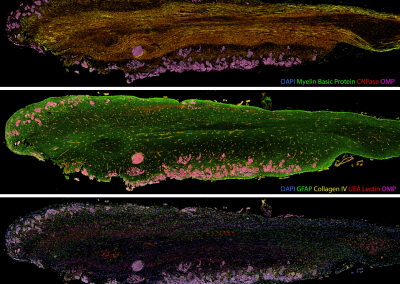

Painting the brain: multiplexed tissue labelling of human brain tissue to facilitate discoveries in neuroanatomy

Detecting anomalous matches in professional sports: a novel approach using advanced anomaly detection techniques

Benefits of linking routine medical records to the GUiNZ longitudinal birth cohort: Childhood injury predictors

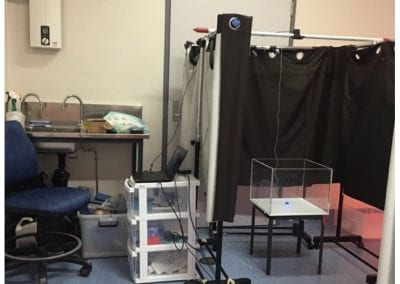

Using a virtual machine-based machine learning algorithm to obtain comprehensive behavioural information in an in vivo Alzheimer’s disease model

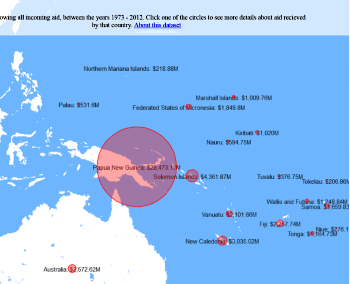

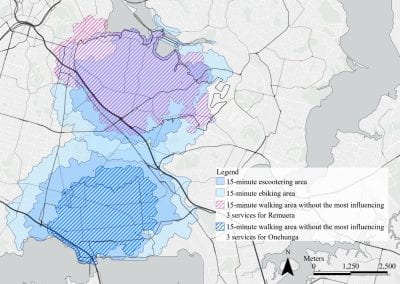

Mapping livability: the “15-minute city” concept for car-dependent districts in Auckland, New Zealand

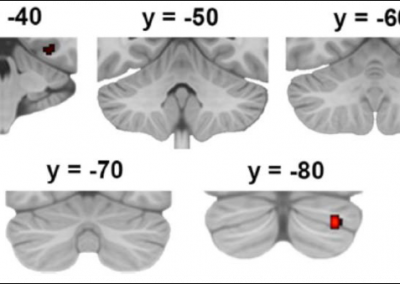

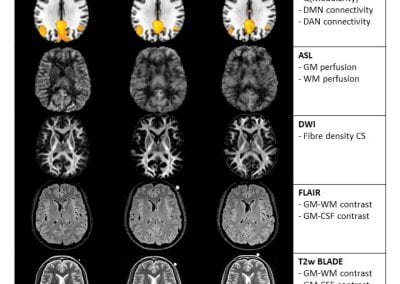

Travelling Heads – Measuring Reproducibility and Repeatability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Dementia

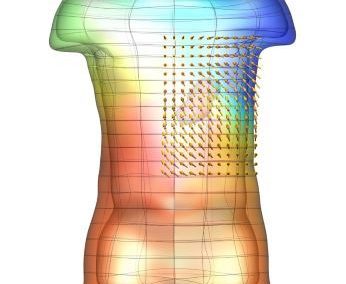

Novel Subject-Specific Method of Visualising Group Differences from Multiple DTI Metrics without Averaging

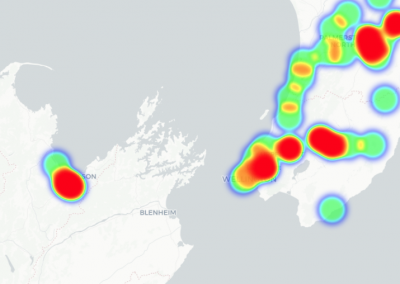

Re-assess urban spaces under COVID-19 impact: sensing Auckland social ‘hotspots’ with mobile location data

Aotearoa New Zealand’s changing coastline – Resilience to Nature’s Challenges (National Science Challenge)

Proteins under a computational microscope: designing in-silico strategies to understand and develop molecular functionalities in Life Sciences and Engineering

Coastal image classification and nalysis based on convolutional neural betworks and pattern recognition

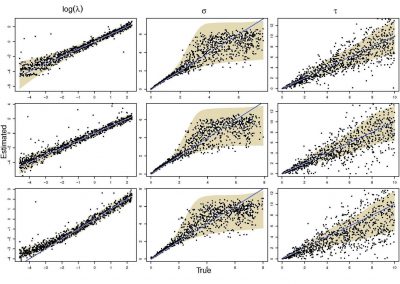

Determinants of translation efficiency in the evolutionarily-divergent protist Trichomonas vaginalis

Measuring impact of entrepreneurship activities on students’ mindset, capabilities and entrepreneurial intentions

Using Zebra Finch data and deep learning classification to identify individual bird calls from audio recordings

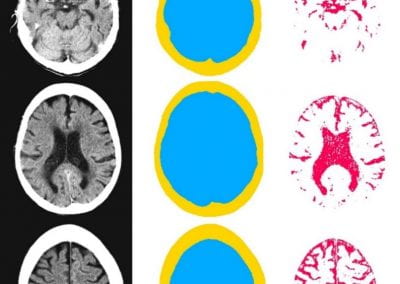

Automated measurement of intracranial cerebrospinal fluid volume and outcome after endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke

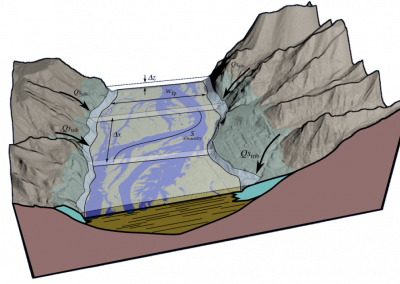

Using simple models to explore complex dynamics: A case study of macomona liliana (wedge-shell) and nutrient variations

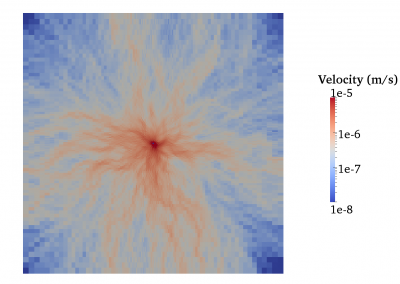

Fully coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modelling of permeability enhancement by the finite element method

Modelling dual reflux pressure swing adsorption (DR-PSA) units for gas separation in natural gas processing

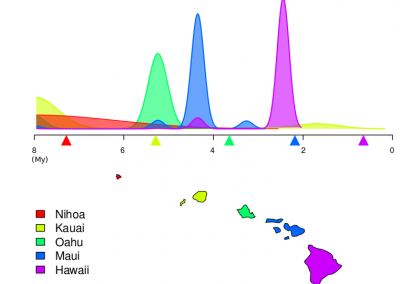

Molecular phylogenetics uses genetic data to reconstruct the evolutionary history of individuals, populations or species

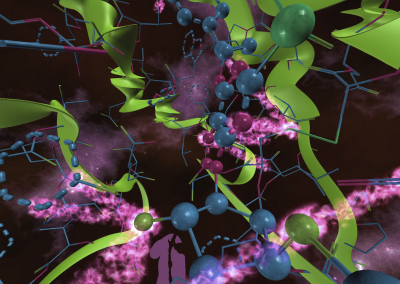

Wandering around the molecular landscape: embracing virtual reality as a research showcasing outreach and teaching tool