The new Wanhal catalogue

Halvor Hosar, PhD Candidate, Associate Professor Allan Badley, School of Music, University of Auckland.

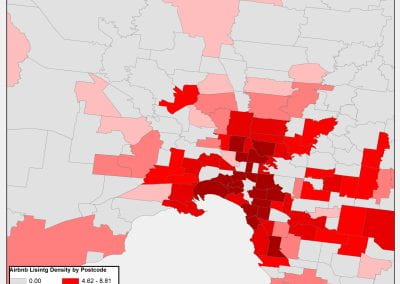

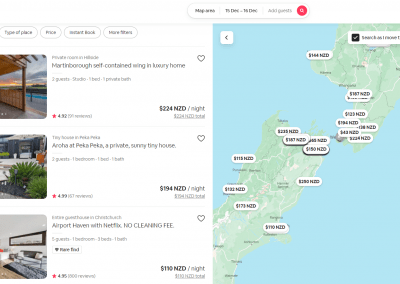

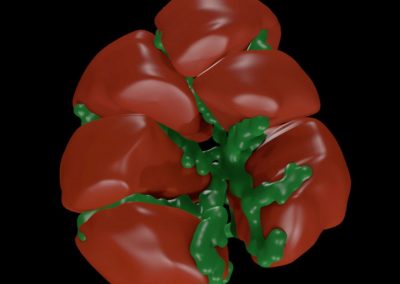

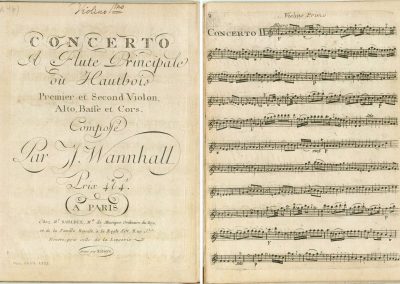

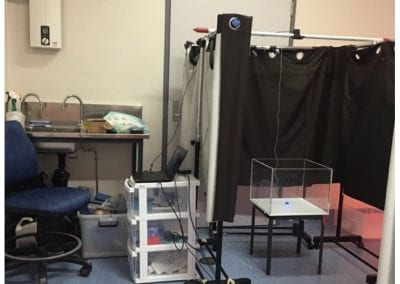

Figure 3. Examples of Wanhal sheet music

Overview

One of the main concerns of musicology has from its inception been to make sure that historical music is performable today. This entails not only understanding the notation, but also making sense of variations from source to source: music was often transmitted in handwritten manuscripts, rather than prints, well into the nineteenth century, and when dealing with such sources, transmission errors were almost unavoidable. In addition, a work could often be changed significantly to suit the needs of the performers.

It is therefore necessary to create source catalogues. These list up the surviving sources where a particular piece of music may be found, and the content and condition of different sources. This facilitates the process of deciding which source or sources to work with when publishing a new edition of a piece, or which version performers playing for historical sources should use, by showing which sources are incomplete, contain significant internal variations and similar details. In addition to the musical sources themselves, such catalogues often try to collect other known facts, such as dates of composition, letters or other texts mentioning particular works and so forth. In this way they are invaluable sources for music performance, publications and research alike.

The works of Wanhal

Johann Baptist Wanhal (Figure 1) was one of the leading minor Viennese classic composers, esteemed by both Haydn and Mozart. Despite never holding a position in church, he wrote more sacred music than any of his Viennese contemporaries, pointing not only towards an innate religiosity but also to connections in the church in the Bohemian lands, where most of his sacred music survives. Sacred music was the last to make the leap to print: of Wanhal’s almost 300 sacred works only four were printed in his lifetime.

Figure 1. Johann Baptiste Wanhal (1739 – 1813)

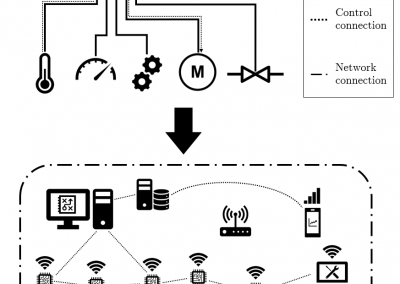

Figure 2. A screenshot from the MerMEId editor.

Composers such as Wanhal have proven highly problematic for cataloguers: the sheer number (see Table 1) and geographic distance between sources makes the work of creating a catalogue a highly problematic business, as it is practically impossible to look at every work in question. As an example, Alexander Weinmann’s catalogue of Wanhal’s non-symphonic works that he began in the 1950’s was still unfinished at his death in 1987, and the resulting catalogue has never been considered satisfactory.

Creating a digital solution with the Centre for eResearch

Digital solutions solve many of the problems associated with the old paper catalogue. Where these had to be finished before going into print, digital solutions may be updated over time.

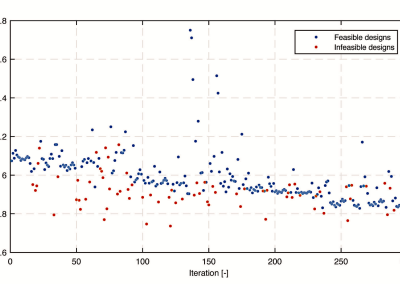

Examples of metadata recognised and recorded by the system include general title, identifier and text blocks, source metadata, Musical structure and instrumentation metadata, Performance data, bibliography and external resources links (Figure 3).

The new Wanhal catalogue greatly simplifies the writing process and makes the catalogue useful even as it is being worked out, potentially making an already useful tool available decades before it can be considered a finished product. It will at first only contain the locations of different sources, which may then be studied by local experts later.

Useful Resources

Geertinger, Axel Teich & Pugin, Laurent: MEI for bridging the gap between music cataloguing and digital critical edition. Die Tonkunst 5/3 (July 2011), pp. 289-294

Table 1. An approximate tally of Wanhal’s works

See more case study projects

Our Voices: using innovative techniques to collect, analyse and amplify the lived experiences of young people in Aotearoa

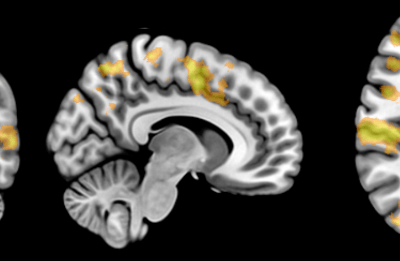

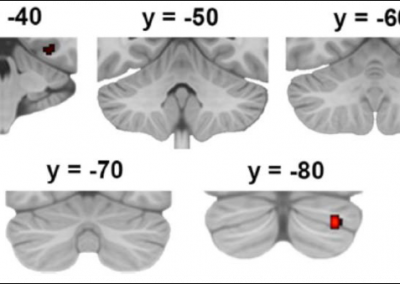

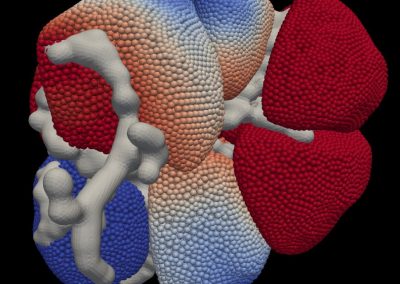

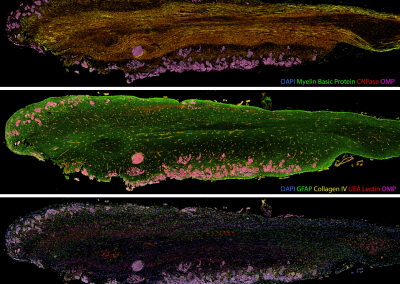

Painting the brain: multiplexed tissue labelling of human brain tissue to facilitate discoveries in neuroanatomy

Detecting anomalous matches in professional sports: a novel approach using advanced anomaly detection techniques

Benefits of linking routine medical records to the GUiNZ longitudinal birth cohort: Childhood injury predictors

Using a virtual machine-based machine learning algorithm to obtain comprehensive behavioural information in an in vivo Alzheimer’s disease model

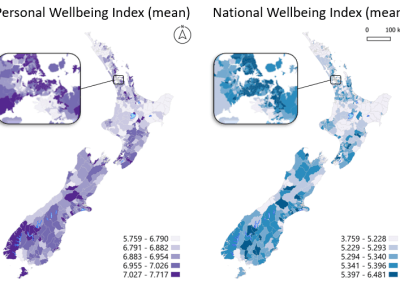

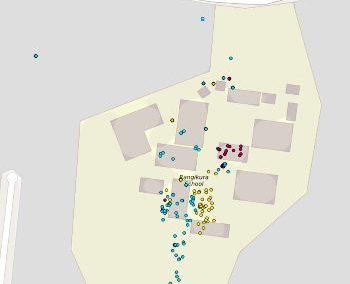

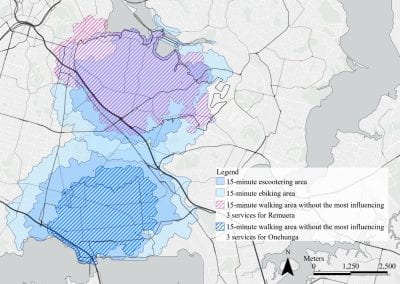

Mapping livability: the “15-minute city” concept for car-dependent districts in Auckland, New Zealand

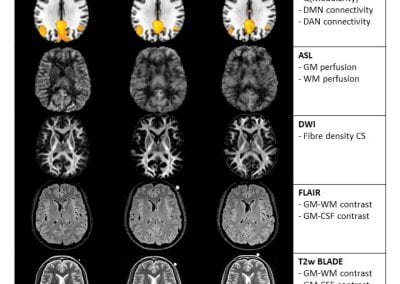

Travelling Heads – Measuring Reproducibility and Repeatability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Dementia

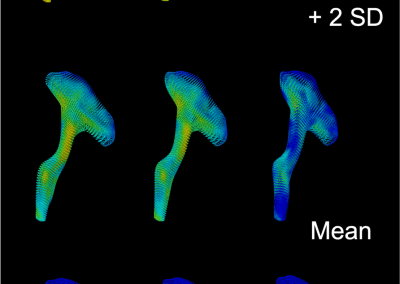

Novel Subject-Specific Method of Visualising Group Differences from Multiple DTI Metrics without Averaging

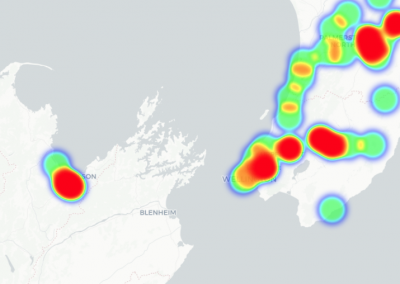

Re-assess urban spaces under COVID-19 impact: sensing Auckland social ‘hotspots’ with mobile location data

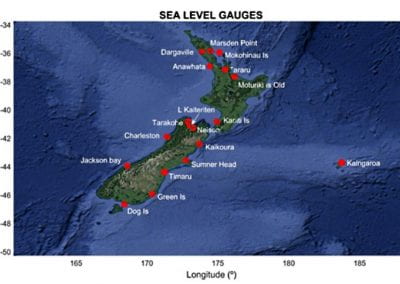

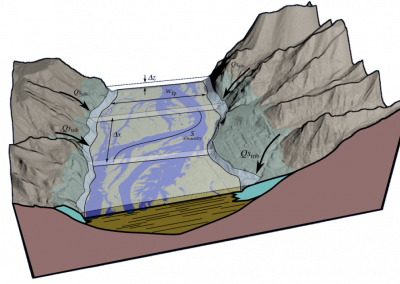

Aotearoa New Zealand’s changing coastline – Resilience to Nature’s Challenges (National Science Challenge)

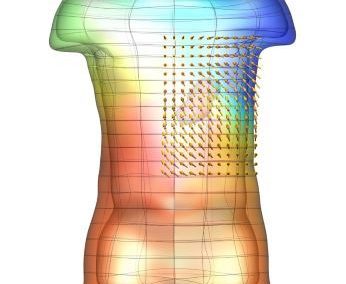

Proteins under a computational microscope: designing in-silico strategies to understand and develop molecular functionalities in Life Sciences and Engineering

Coastal image classification and nalysis based on convolutional neural betworks and pattern recognition

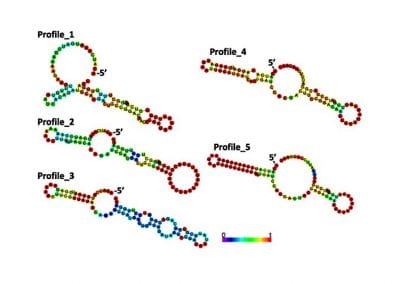

Determinants of translation efficiency in the evolutionarily-divergent protist Trichomonas vaginalis

Measuring impact of entrepreneurship activities on students’ mindset, capabilities and entrepreneurial intentions

Using Zebra Finch data and deep learning classification to identify individual bird calls from audio recordings

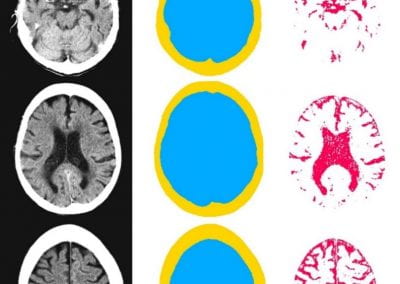

Automated measurement of intracranial cerebrospinal fluid volume and outcome after endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke

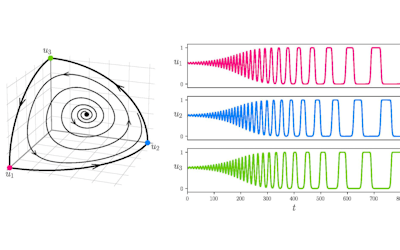

Using simple models to explore complex dynamics: A case study of macomona liliana (wedge-shell) and nutrient variations

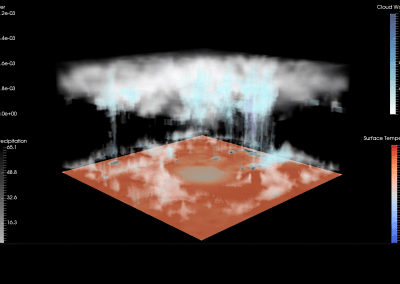

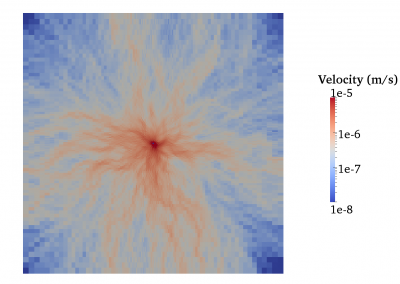

Fully coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modelling of permeability enhancement by the finite element method

Modelling dual reflux pressure swing adsorption (DR-PSA) units for gas separation in natural gas processing

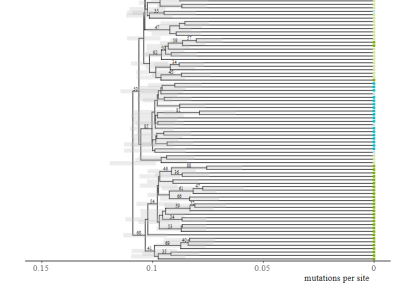

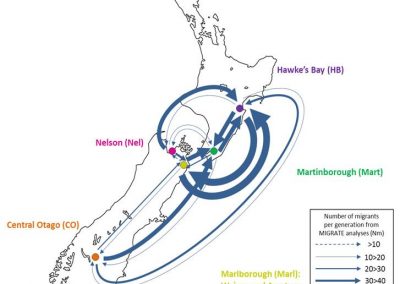

Molecular phylogenetics uses genetic data to reconstruct the evolutionary history of individuals, populations or species

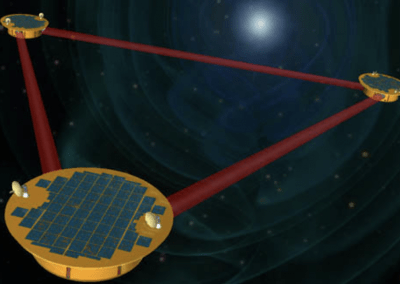

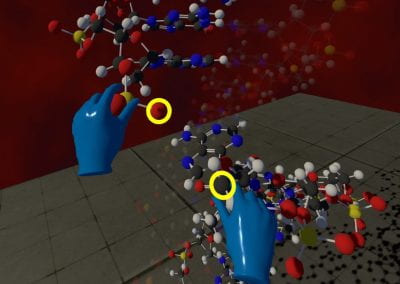

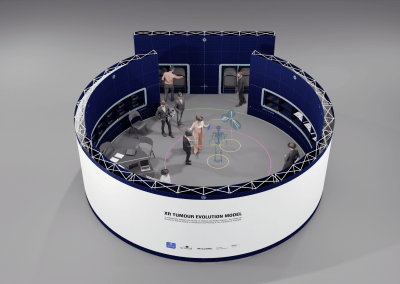

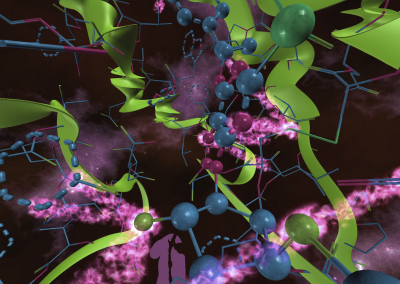

Wandering around the molecular landscape: embracing virtual reality as a research showcasing outreach and teaching tool