Using simple models to explore complex dynamics: A case study of macomona liliana (wedge-shell) and nutrient variations

K.R.Bryan, G. Coco, S.T. Thrush, C.A Pilditch, School of Environment

Introduction to tipping points: A dynamical tipping point

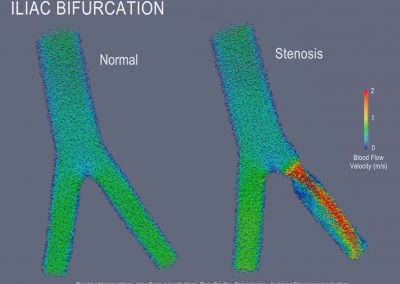

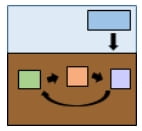

Ecosystem behaviour can be non-linear which means that small changes in environmental conditions can cause disproportionately large changes in response leading to unexpected regime shifts or catastrophic collapses. It also means that the different states can occur when the environmental conditions are the same (alternative stable states). Multiples stressors (eg, sediment change or nutrient loading) can further accentuate the nonlinearities in the system ultimately leading to loss of resilience and increased susceptibility to change.

A dramatic response forced event

Tipping or regime shifts are not the same as catastrophic changes to ecosystems following extreme events such as e.g. floods or volcanic eruptions.

How are simple models useful for exploring change and assessing risk

- Defining the conditions leading to a tipping point, e.g. Increase in variability

- Differentiating between tipping points and a delayed response to change.

- Determining what happens during a tipping event so that key pathways can be made more resilient.

- Determining which aspects should be restored, and the potential response to restoration.

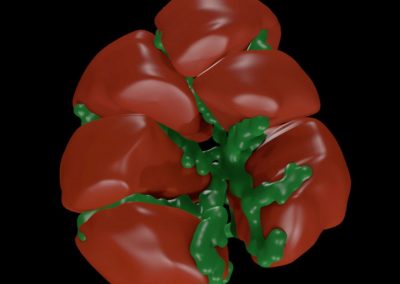

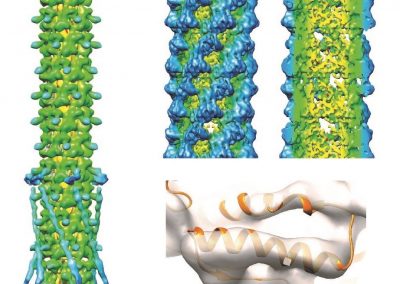

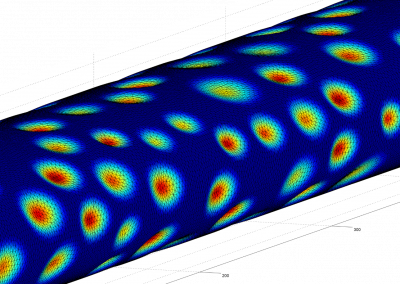

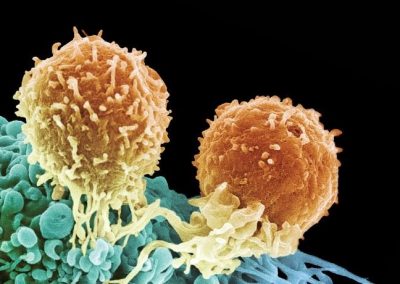

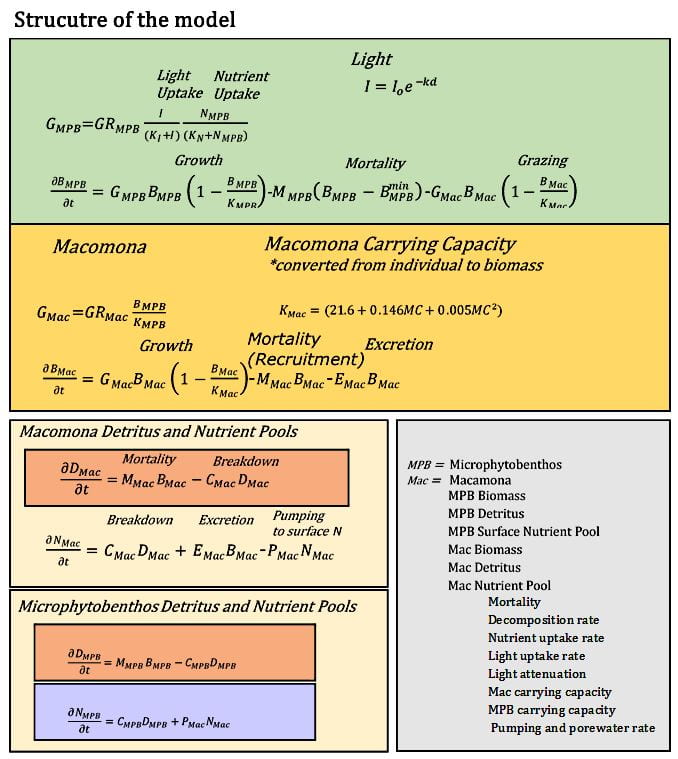

The simple system that we have chosen to model is the interaction between Macomona liliana and microphytobenthos (MPB). Macomona. Macomona live within the sediments, but feed at the surface. The detritus and nutrients that they produce within the sediments can only reach the surface by porewater movement or Mcaomona pumping behaviour. This can limit the supply of nutrients to MPB.

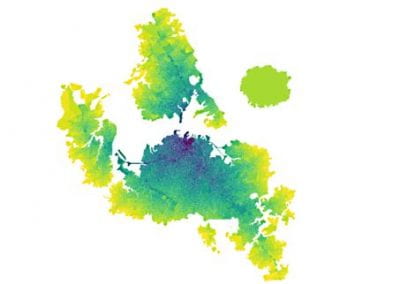

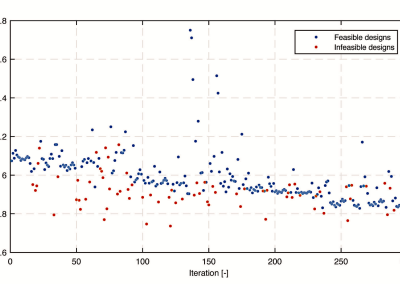

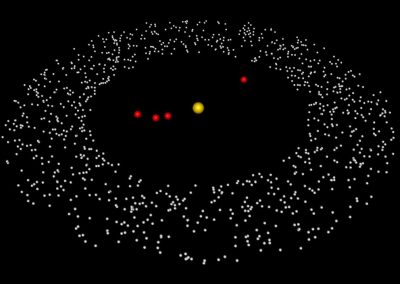

Preliminary results: Alternative States

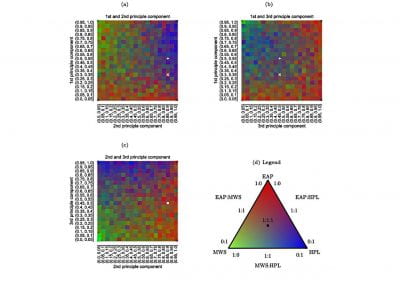

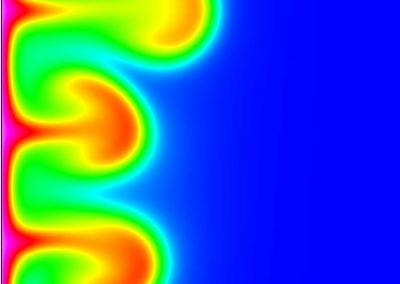

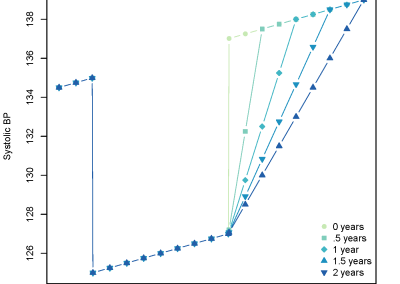

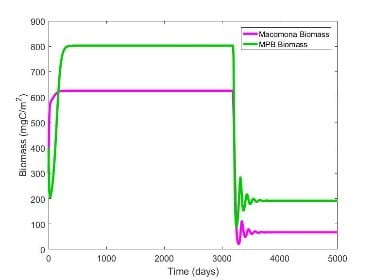

High nutrient: Shifting regimes

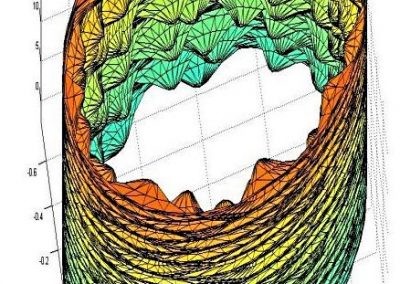

The stable MPB and Macomona biomass is established at the carrying capacity of the system. After some time, the nutrients accumulate at depth and replenishment to the surface is limited by the flushing rate. These nutrients eventually become toxic and cause the Macomona population to collapse. Reduced grazing pressure and nutrient supply means the MPB population establishes at a new level.

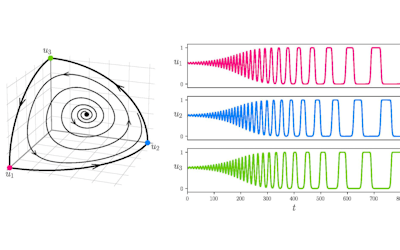

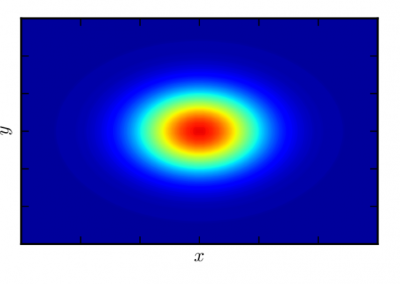

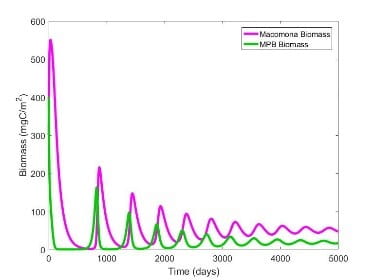

Low nutrients: tight non-linear coupling

In a low nutrient environment, the MPB quickly use the surface nutrient supply, and their biomass collapses. The Macomona follows after a short time lag. The detrital pool breaks down, and supplies a new source of nutrient, which causes MPB to recover. Gradually through time, the oscillations diminish. Eventually a stable state will be established.

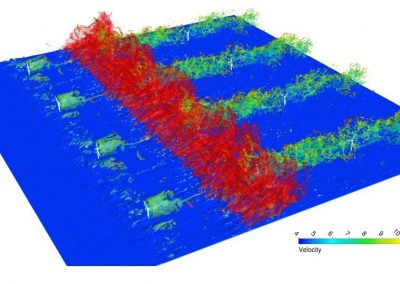

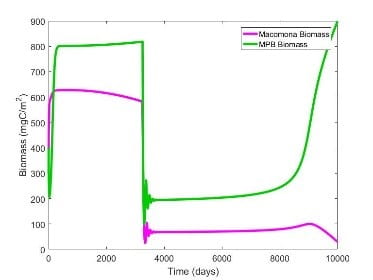

Sediment composition change: multiple stressors cause catastrophic shifts

Changes toward muddier sediments feed back into reducing the Macomona carrying capacity. The increasing Macomona detrital pool eventually leads to toxic levels of nutrients at depth, ultimately removing Macomona completely. The MPB re-establishes subsisting on external nutrients and its own regenerated supply.

Next Step

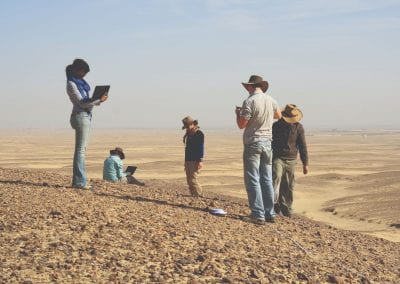

- Improvde parameterisations from field experiements

- Analyse observations to detect similar state changes

Acknowledgement

- Funding from Sustainable Seas is gratefully acknowledged

- Judi Hewitt,Rebecca Gladstone-Gallagher, Georgina Flowers, Julie Hope, Sally Woodin and Dave Weathey for insightful discussions.

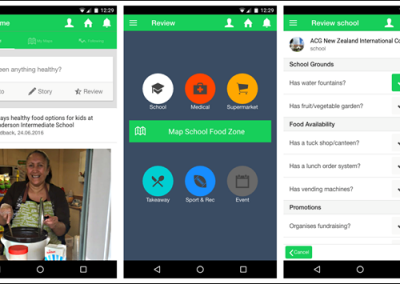

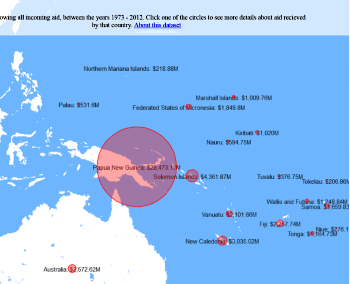

Nick Young from The Centre for eResearch contributed an online, interactive, ecological simulator for the interactions between Macomona liliana and Microphytobenthos. Click here.

See more case study projects

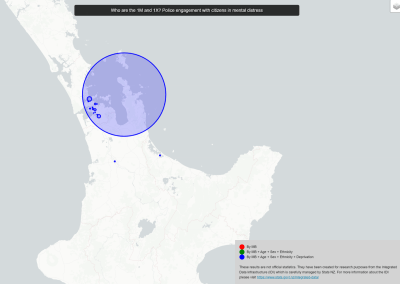

Our Voices: using innovative techniques to collect, analyse and amplify the lived experiences of young people in Aotearoa

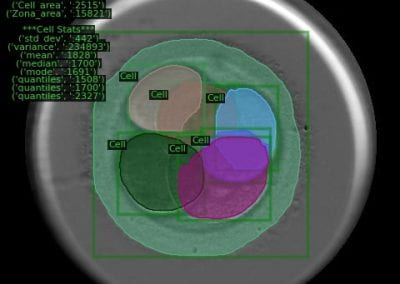

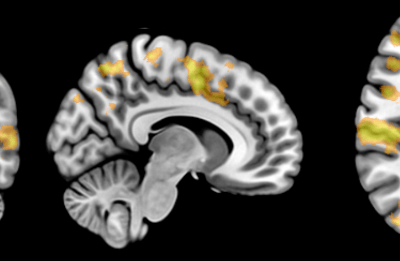

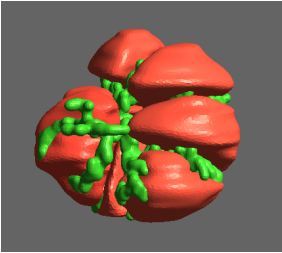

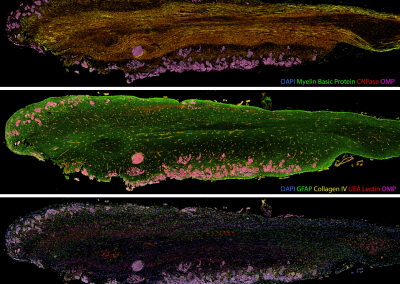

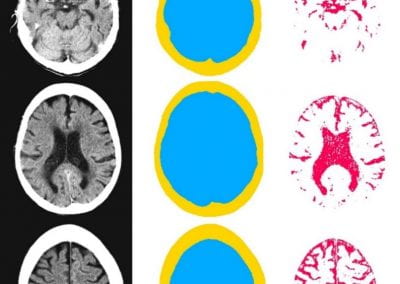

Painting the brain: multiplexed tissue labelling of human brain tissue to facilitate discoveries in neuroanatomy

Detecting anomalous matches in professional sports: a novel approach using advanced anomaly detection techniques

Benefits of linking routine medical records to the GUiNZ longitudinal birth cohort: Childhood injury predictors

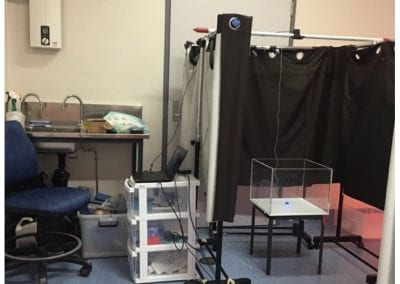

Using a virtual machine-based machine learning algorithm to obtain comprehensive behavioural information in an in vivo Alzheimer’s disease model

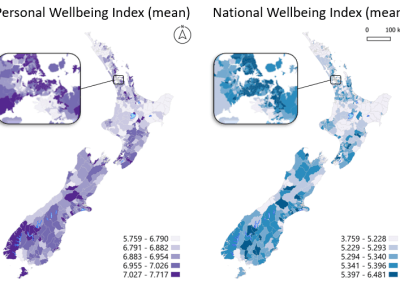

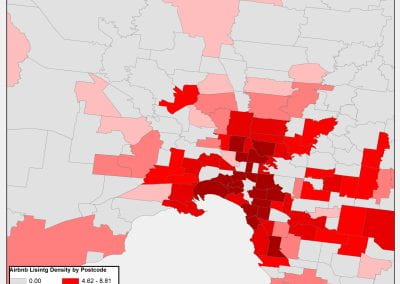

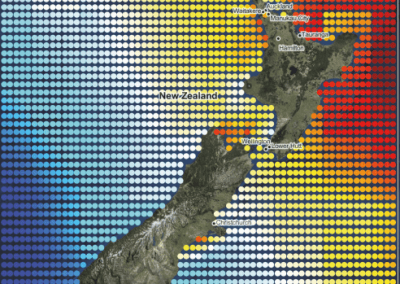

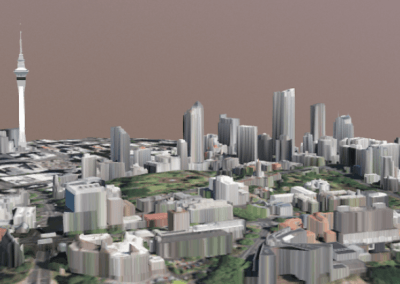

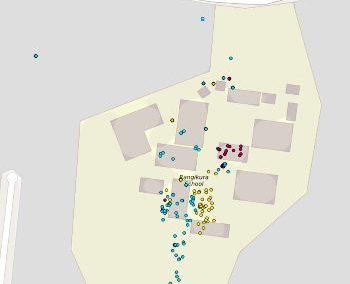

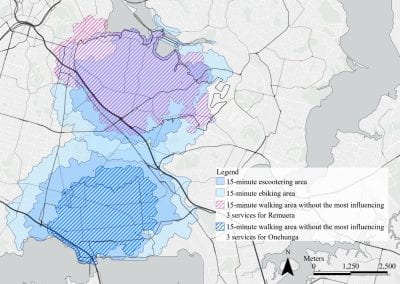

Mapping livability: the “15-minute city” concept for car-dependent districts in Auckland, New Zealand

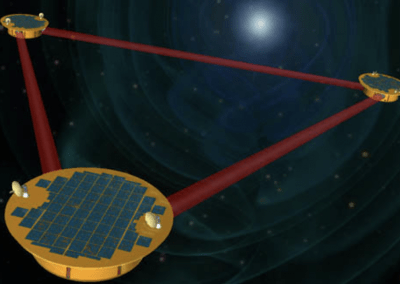

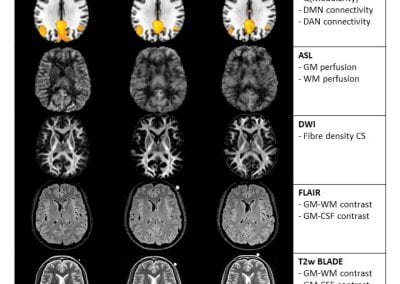

Travelling Heads – Measuring Reproducibility and Repeatability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Dementia

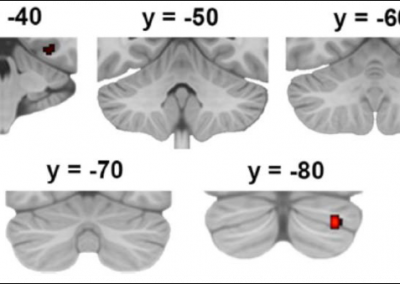

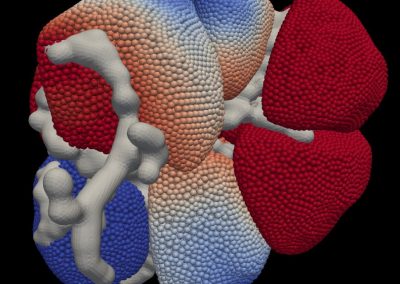

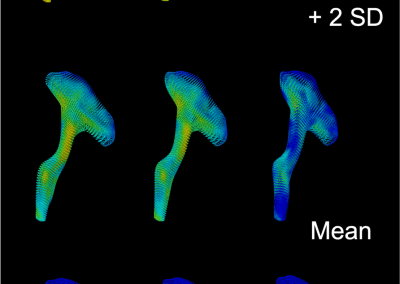

Novel Subject-Specific Method of Visualising Group Differences from Multiple DTI Metrics without Averaging

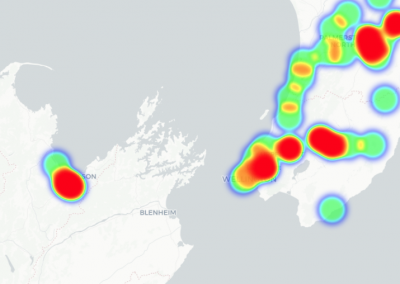

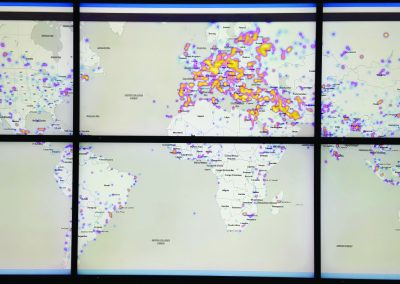

Re-assess urban spaces under COVID-19 impact: sensing Auckland social ‘hotspots’ with mobile location data

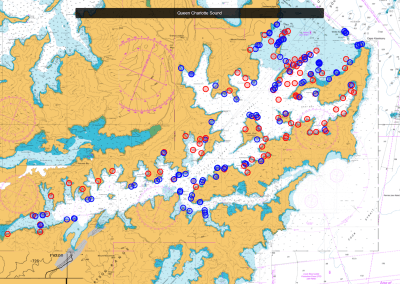

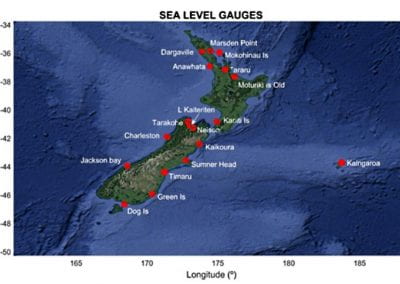

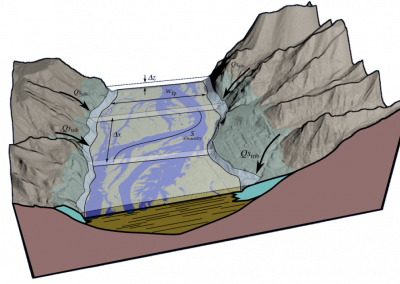

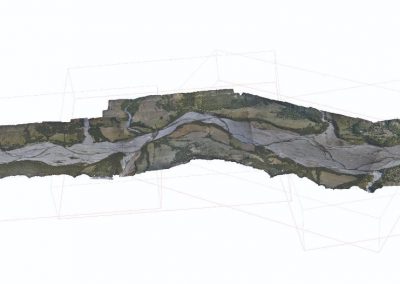

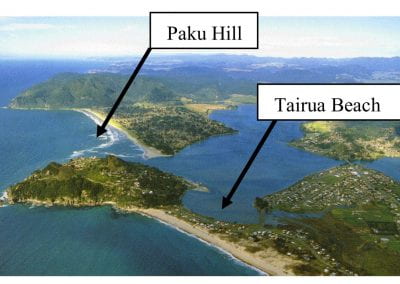

Aotearoa New Zealand’s changing coastline – Resilience to Nature’s Challenges (National Science Challenge)

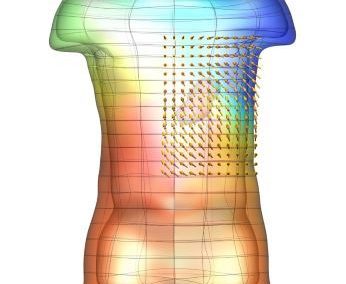

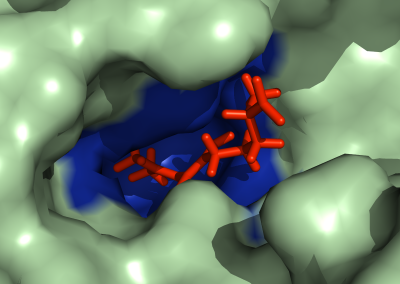

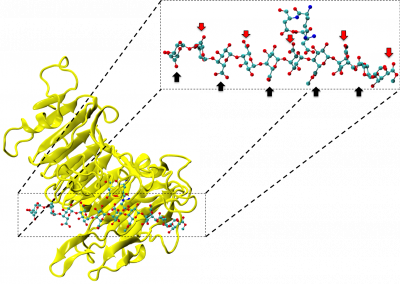

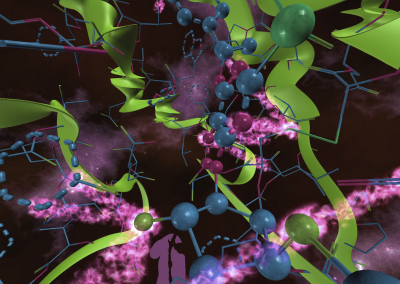

Proteins under a computational microscope: designing in-silico strategies to understand and develop molecular functionalities in Life Sciences and Engineering

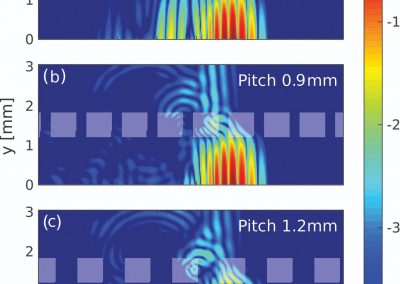

Coastal image classification and nalysis based on convolutional neural betworks and pattern recognition

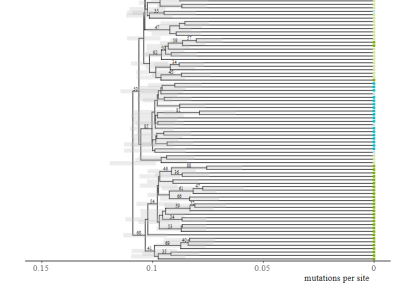

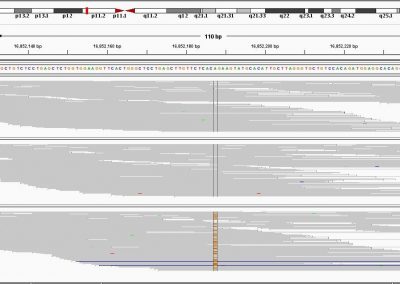

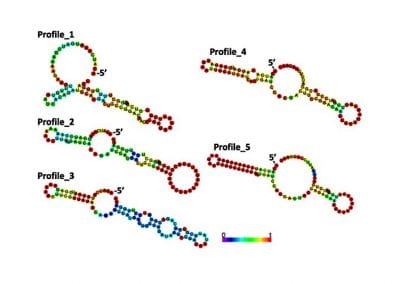

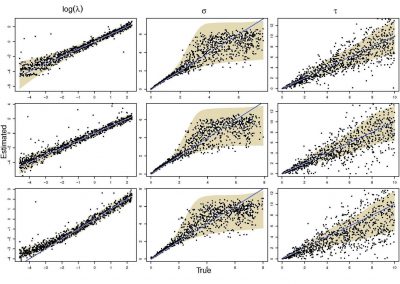

Determinants of translation efficiency in the evolutionarily-divergent protist Trichomonas vaginalis

Measuring impact of entrepreneurship activities on students’ mindset, capabilities and entrepreneurial intentions

Using Zebra Finch data and deep learning classification to identify individual bird calls from audio recordings

Automated measurement of intracranial cerebrospinal fluid volume and outcome after endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke

Using simple models to explore complex dynamics: A case study of macomona liliana (wedge-shell) and nutrient variations

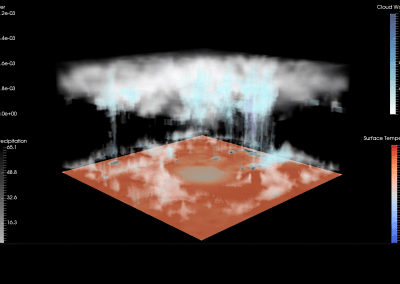

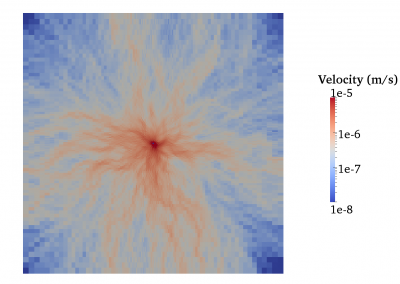

Fully coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modelling of permeability enhancement by the finite element method

Modelling dual reflux pressure swing adsorption (DR-PSA) units for gas separation in natural gas processing

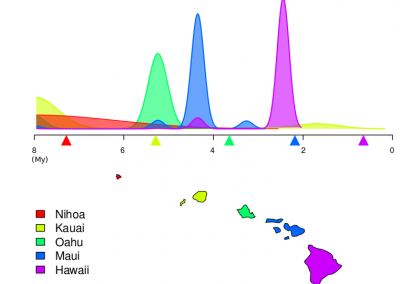

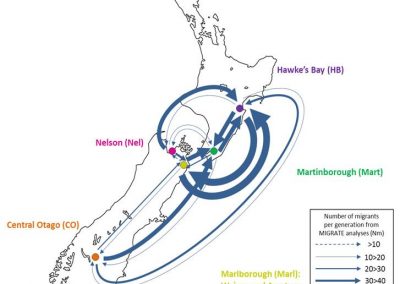

Molecular phylogenetics uses genetic data to reconstruct the evolutionary history of individuals, populations or species

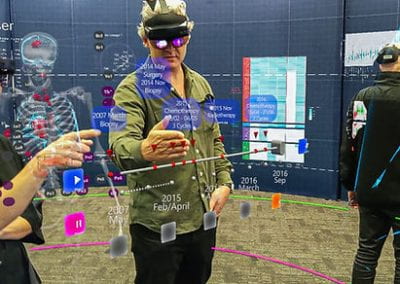

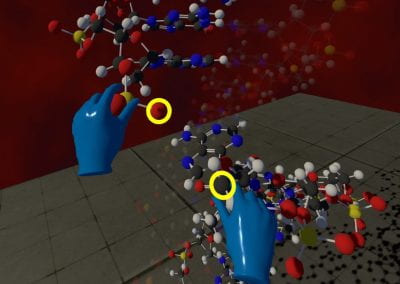

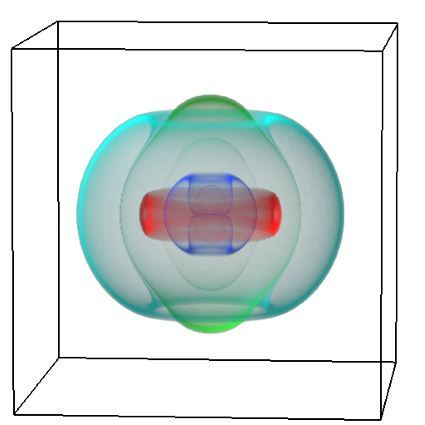

Wandering around the molecular landscape: embracing virtual reality as a research showcasing outreach and teaching tool